Table of contents

Asset minification (CSS, JS, HTML)

A slow page is rarely slow for just one reason – but unminified assets are one of the easiest ways to "pay" extra bytes on every single visit. For e-commerce and lead gen sites, that tax shows up as fewer product views per session, lower conversion rates on mobile, and more spend to buy the same revenue.

Asset minification means removing unnecessary characters from CSS, JavaScript, and HTML (whitespace, comments, long variable names, optional syntax) so files are smaller and usually faster to parse. It does not change what the code does – only how it's represented.

What minification reveals

Minification is less about chasing a vanity "smaller file" number and more about answering a practical question:

Are you shipping more bytes than users need to see and use the page?

Minification affects performance in three places:

- Download time (network): fewer bytes to transfer, especially noticeable on mobile and in high-latency regions.

- Decompression and parsing (CPU): browsers still have to parse CSS/JS/HTML; smaller inputs generally parse faster.

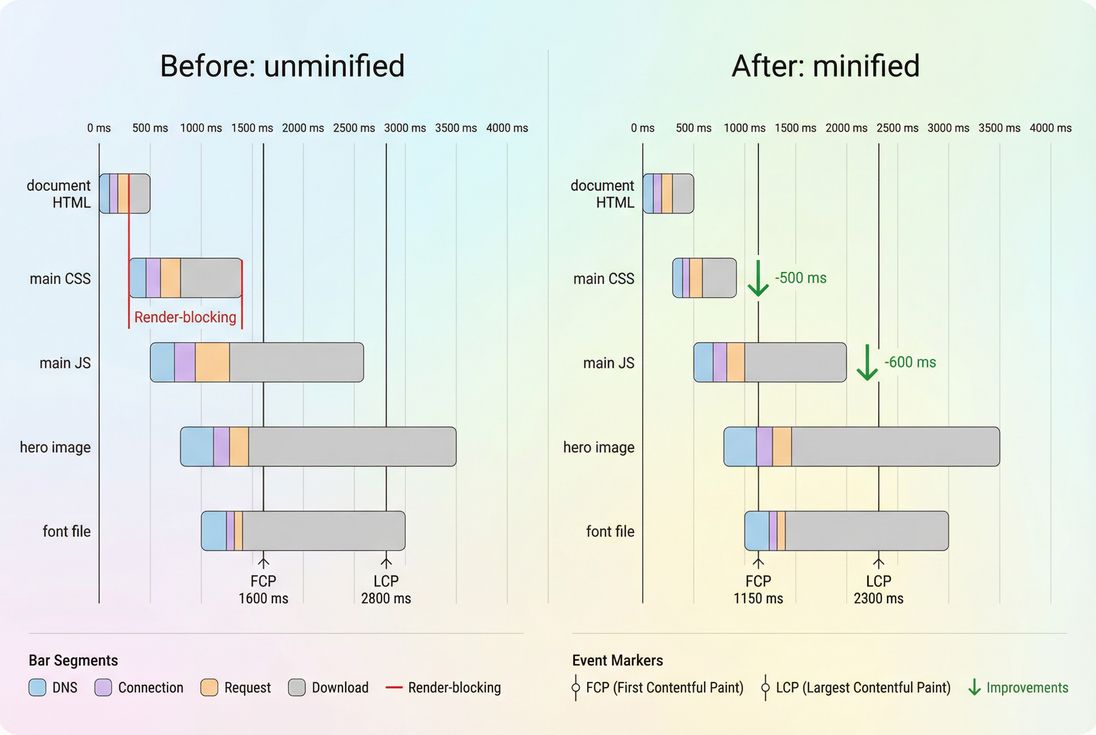

- Rendering and interactivity timing: if the assets are render-blocking or delay the main thread, smaller files can move metrics like FCP, LCP, and responsiveness indicators tied to main-thread work (see JS execution time and Long tasks).

Where website owners get tripped up: minification is often worth doing, but it's not always the biggest lever. If your real bottleneck is render-blocking CSS, heavy third-party scripts, or slow server response, minification alone won't "fix" the page. It's foundational hygiene – then you move to higher-impact work like Unused JavaScript, Unused CSS, and Code splitting.

The Website Owner's perspective

If minification is missing, you're paying a permanent performance surcharge on every visit. It's the kind of issue that quietly inflates bounce rate and ad costs over time because every campaign sends traffic to a heavier-than-necessary page.

How savings are measured

Minification is usually evaluated as potential byte savings between an unminified and minified version of the same resource.

In real audits (like Lighthouse-based tooling), you'll see something like:

- A list of CSS/JS resources that appear unminified

- The original resource size

- The estimated savings if minified

Two important clarifications for interpreting those numbers:

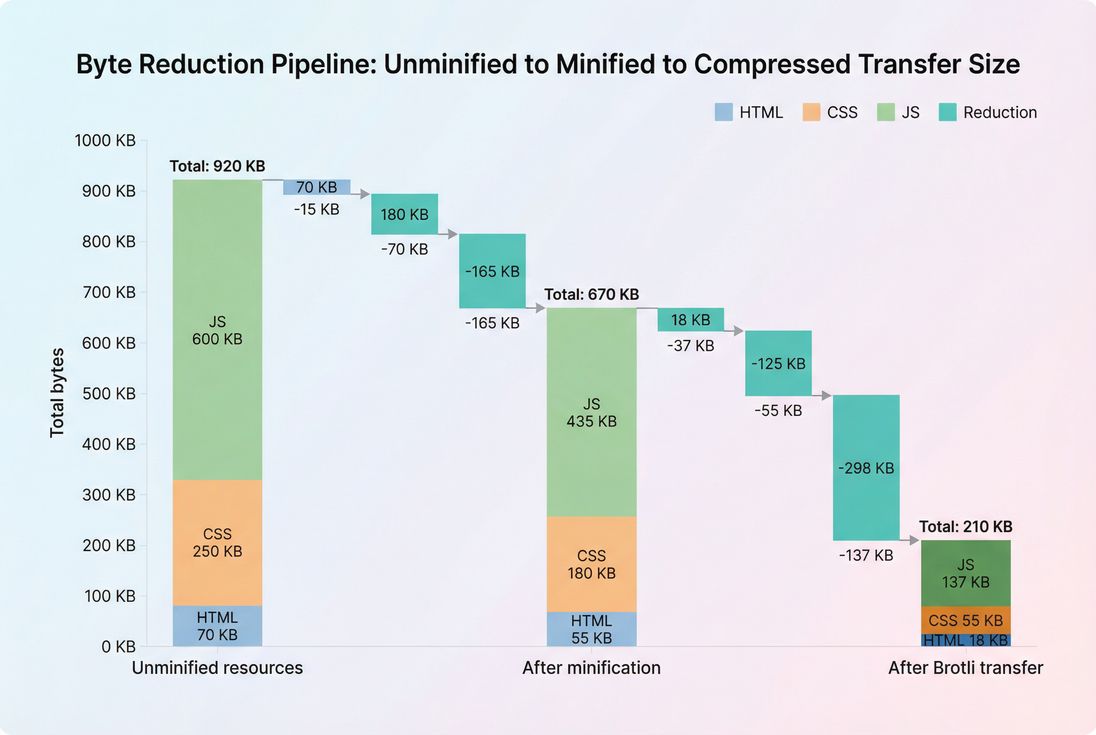

1) "Raw size" vs "transferred size"

- Raw size is the number of bytes in the file itself.

- Transferred size is what actually goes over the network after Brotli compression or Gzip compression.

Minification reduces raw size. Compression reduces transferred size. You typically want both.

2) Minification is not the same as removing code

Minification removes "textual overhead." It does not remove functionality. If your bundle contains a full date library, three UI component frameworks, and unused checkout code on the homepage, minification won't remove those costs. That's the job of:

Minification reduces raw bytes; compression reduces transferred bytes. Both matter, but JavaScript usually dominates the opportunity.

Practical benchmarks (what "good" looks like)

These are rough expectations for modern sites:

| Asset type | Typical minification savings (raw) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HTML | 5–20% | Higher if templates ship lots of whitespace/comments |

| CSS | 10–30% | Higher if you have verbose formatting or long class names |

| JavaScript | 10–35% | Higher if code is not already bundled/minified; lower if modern build already optimized |

If you're already serving production bundles (minified + compressed), Lighthouse "minify" findings should be near zero except for third-party scripts or misconfigurations.

When minification actually moves the needle

Minification matters most when it reduces bytes on the critical path – the resources that must load before the browser can render meaningful content or respond quickly.

Render-blocking CSS and early JS

If your page's CSS is render-blocking (common), cutting CSS bytes can improve how quickly the browser can paint content. This is closely tied to the Critical rendering path and Render-blocking resources.

If your page ships a large JavaScript bundle early, minification can help in two ways:

- less download time

- less parse time before execution begins

But if your real issue is execution (framework hydration, heavy third-party scripts), minification alone may not improve responsiveness. That's when to focus on Reduce main thread work and analyze Third-party scripts.

Mobile users and paid traffic

Minification is disproportionately valuable when:

- a large share of sessions are on mobile (see Mobile page speed)

- you buy traffic and pay per click (every extra second lowers conversion)

- you operate internationally (higher network latency and RTT)

The Website Owner's perspective

If you're spending on ads, unminified assets are like paying for clicks to a heavier landing page. You're not just losing speed – you're lowering the conversion rate of traffic you already paid for.

High-request-count pages

Minification helps more when you ship many small files (common with legacy setups) because each file has overhead and may not compress optimally. That said, don't "solve" this by concatenating everything into one huge bundle; modern best practice is fewer critical files, plus code splitting for the rest.

When you should expect little change

Minification may not show much user impact when:

- your bottleneck is slow backend or high TTFB

- assets are already minified and compressed

- LCP is dominated by images (then look at Image optimization and Image formats WebP vs AVIF)

- the real problem is layout shifting (see CLS) or responsiveness (see INP)

How to tell if you're really minifying

Many teams assume "our framework handles that," then discover production is serving a dev build.

Here's a fast, reliable checklist:

- Inspect resource URLs: production assets typically include

.min.css/.min.jsor hashed filenames (e.g.,app.3f2c1.js). Naming isn't proof, but it's a hint. - Check response headers: confirm

content-encoding: bror gzip (see Brotli compression and Gzip compression). - Open the file: minified files are usually one long line or very few lines, with short variable names.

- Confirm caching is sane: minified assets are often static and should be cached aggressively (see Browser caching and Cache-Control headers).

- Validate source maps behavior: source maps should help debugging but should not become large downloadable JS "by accident."

If you're using PageVitals' Lighthouse reporting or test artifacts, the quickest way to confirm is to look at the exact resource URLs flagged and then inspect them in the network request waterfall (see /docs: Network request waterfall and Lighthouse tests).

Minifying critical CSS/JS can shorten render-blocking time and pull FCP/LCP earlier – especially on slower connections.

How to implement minification safely

The safest approach is: minify in your build step, not ad hoc on the server, and validate with automated testing. Below are practical guardrails per asset type.

CSS minification

CSS minifiers typically:

- remove whitespace and comments

- shorten color values where safe

- simplify certain expressions

- merge duplicate rules (depending on tooling)

Common gotchas:

- Over-aggressive merging can change specificity edge cases in messy CSS.

- If you inline "critical CSS" into HTML, you still need to maintain minification discipline (see Critical CSS and Above-the-fold optimization).

Practical advice:

- Minify the output bundle, not scattered source files.

- Pair minification with unused CSS removal for bigger wins (see Unused CSS).

JavaScript minification

JS minifiers often:

- remove whitespace/comments

- shorten identifiers (mangling)

- drop unreachable branches (basic dead code elimination)

- sometimes inline constants (depending on settings)

Common gotchas:

- Modern syntax support: make sure the minifier supports your JS syntax and target browsers.

- Third-party code: some vendors ship already minified; others do not. You might not be allowed to alter it.

- Debug builds shipped to prod: a single misconfigured environment can ship unminified bundles and blow up performance.

Practical advice:

- Minification is baseline; then focus on what you're shipping:

- remove unused code (Unused JavaScript)

- split bundles (Code splitting)

- reduce blocking behavior with Async vs defer

HTML minification

HTML minification often:

- removes whitespace and comments

- collapses optional closing tags (depending on tool)

- minifies inline

<style>and<script>blocks (sometimes)

Common gotchas:

- Whitespace can be meaningful in certain contexts (e.g.,

<pre>, inline text nodes, some templating edge cases). - Inline scripts/styles can break if the minifier is not context-aware.

Practical advice:

- Minify HTML at build/render time (static generation) or via a safe middleware.

- If you inject large JSON blobs into HTML (state hydration), minification helps a bit – but the bigger question is whether you should ship that much state at all.

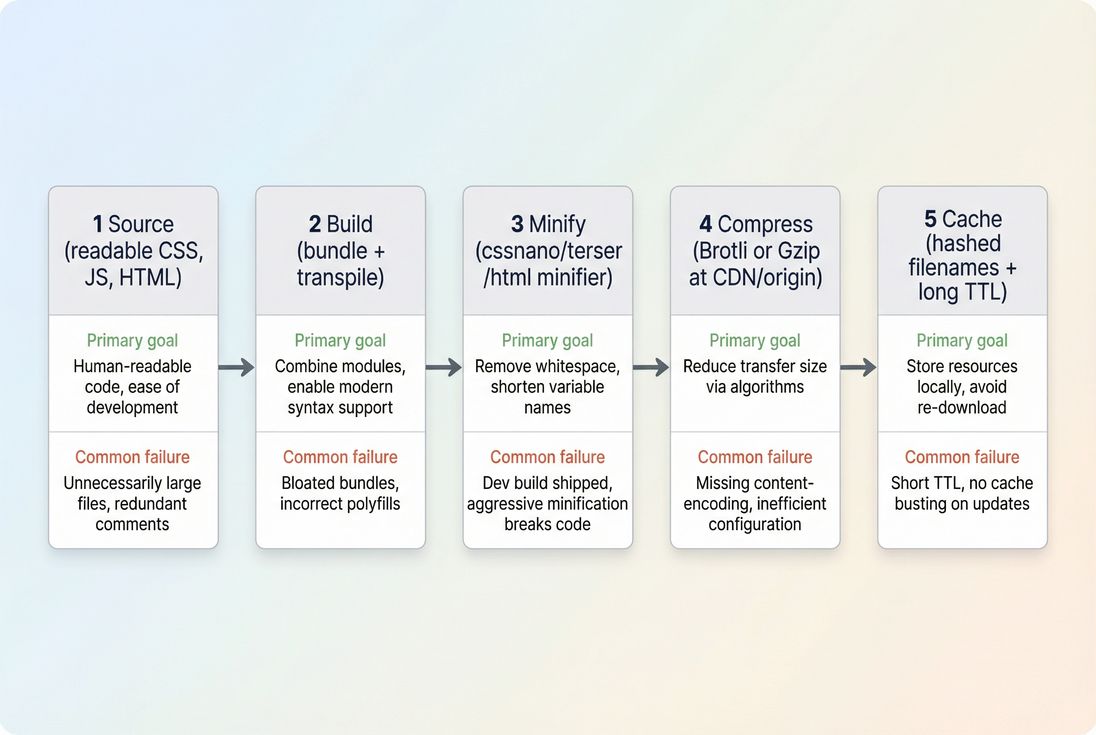

A production-safe pipeline

Minification should be one stage in a predictable release pipeline, alongside compression, caching, and verification.

Minification is one step in the delivery chain. It works best when paired with compression, caching, and a repeatable build process.

How website owners should interpret changes

Minification changes are easy to misread unless you tie them to outcomes.

If minified bytes go down

This is usually positive, but confirm:

- Did you reduce critical-path bytes (CSS/early JS), or only noncritical scripts loaded later?

- Did FCP/LCP improve in lab tests, and do you see movement in field data over time? (See Field vs lab data and CrUX data.)

If minified bytes go up

Treat it like a release signal, not automatically a failure:

- A new feature may legitimately add code.

- The real question is whether you added critical code or deferred code.

This is where performance budgets help you make business tradeoffs explicitly (see Performance budgets and /docs: Performance budgets).

If minification savings suddenly reappear

If audits start saying "minify CSS/JS" again after months of clean reports, it often means:

- a deployment started serving a non-production build

- a new third-party tag is unminified

- an A/B testing tool injected unminified code

- a CDN rule stopped compressing certain MIME types

Use a waterfall view to pinpoint the exact requests and confirm headers (see /docs: Network request waterfall).

How to prioritize minification versus bigger wins

A practical ordering that works for most sites:

- Turn on minification everywhere (CSS/JS/HTML) as a baseline.

- Ensure compression is enabled (Brotli compression preferred).

- Fix caching for static assets (Cache-Control headers and Browser caching).

- Reduce render-blocking resources (Render-blocking resources, Critical CSS, Async vs defer).

- Remove unused code and split bundles (Unused JavaScript, Unused CSS, Code splitting).

What this looks like in a real e-commerce scenario:

- If your product detail page ships a 700 KB JS bundle, minification might cut it to ~500 KB raw, but if you only need 200 KB for the initial view, unused code removal + code splitting will usually beat "better minification" every time.

- If your category page is CSS-heavy and render-blocked, minifying and then extracting Critical CSS can move LCP more reliably than touching JS.

The Website Owner's perspective

Minification is a control: it reduces waste. But the business win usually comes from deciding what code should load early at all. Once minification is in place, the next-level question is "what can we avoid shipping on this page?"

Quick action checklist

If you want a fast, high-confidence implementation plan:

- Verify production builds output minified CSS/JS (and not dev builds).

- Ensure HTML is minified safely (especially if SSR templates are verbose).

- Confirm Brotli or gzip is enabled for text assets.

- Check that static assets are cacheable with long TTLs and versioned filenames (see Cache TTL and Edge caching).

- Re-test and validate that any remaining "minify" flags are third-party or exceptional cases – and decide whether they are worth replacing.

Minification won't solve every performance problem, but it removes a permanent penalty. Once it's reliably in place, you can spend your time on the optimizations that actually change how fast users see content and how quickly the site responds.

Frequently asked questions

Minification often saves 5 to 30 percent of raw file size, but the user-visible impact depends on what is blocking rendering and how big the files are. On mobile networks, saving even 50 to 150 KB of JavaScript can reduce render delay and improve LCP and INP.

Yes. Compression reduces transfer size, but minification reduces the bytes that must be downloaded, parsed, and sometimes executed. Minification also helps compression work better by removing noise. If you already use Brotli, the incremental transfer savings may be smaller, but CPU parse savings can still matter.

This usually happens when a specific file is served unminified in production, a third party script is unminified, or your server is returning a debug build. It can also occur if source maps are accidentally served as large JS files. Verify the exact URL in the audit and inspect the response.

Done correctly, minification should not affect SEO or accessibility. The main downside is harder debugging, which you address with source maps and proper release practices. The real risk is breakage from overly aggressive minifiers or HTML whitespace removal in sensitive areas like preformatted text.

Minification is table stakes and should be on by default. After that, removing unused CSS and unused JavaScript usually wins bigger because it reduces entire features you do not need on a page. Code splitting then prevents noncritical code from loading upfront, which often improves LCP and INP more than further minification.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial