Table of contents

Code splitting for faster load times

A "fast" redesign can still lose money if it ships more JavaScript. On e-commerce sites, that usually shows up as slower product page rendering, delayed add-to-cart clicks, and higher bounce from paid traffic – especially on mid-range mobile devices.

Code splitting is the practice of breaking your JavaScript (and sometimes CSS) into smaller "chunks" so the browser downloads and runs only the code needed for the current page and above-the-fold UI, deferring the rest until it's actually required (route change, user interaction, or idle time).

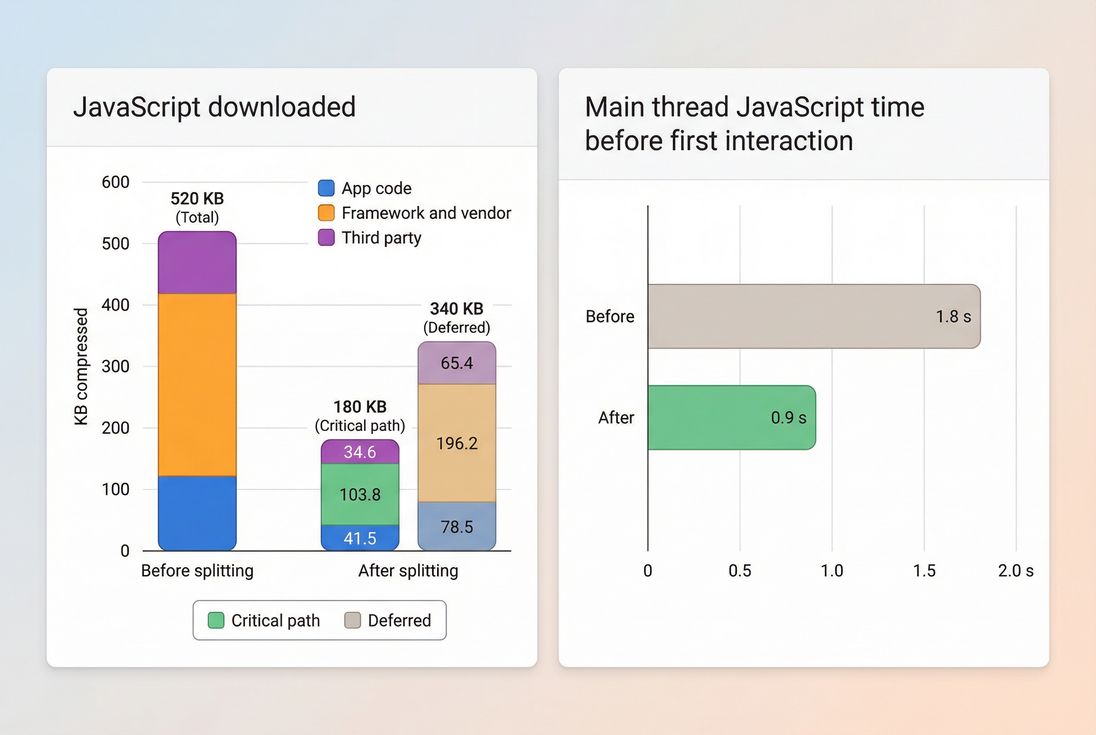

Code splitting pays off when it reduces what's on the critical path: fewer compressed KB to download and less JavaScript time before the page becomes usable.

What code splitting changes

When a page loads, the browser has to do more than download files. For JavaScript-heavy pages it often has to:

- Download the scripts

- Parse them (turn text into executable code)

- Compile and execute them

- Run framework hydration and event wiring

- Handle layout and rendering work triggered by JavaScript

If you ship one big bundle, you're forcing all of that work to happen early – even if the user only needs a small slice of that functionality to see the hero area and start scrolling.

Code splitting changes when code is downloaded and executed:

- Critical path code: required to render above-the-fold content and basic interactions.

- Deferred code: everything else (reviews, carousels, personalization, chat, analytics extras, admin UI, rarely used components).

This has direct impact on the metrics you already track:

- LCP (Largest Contentful Paint): improves when the main thread isn't busy executing nonessential code and the network isn't congested with avoidable JS.

- INP (Interaction to Next Paint): improves when you reduce long tasks and heavy initialization that blocks input handling.

- FCP (First Contentful Paint): can improve if render-blocking scripts are reduced.

- JavaScript-specific diagnostics like bundle size (JS bundle size), execution time (JS execution time), long tasks (Long tasks), and overall main thread work (Reduce main thread work).

The Website Owner's perspective: If the homepage "loads" but the page is unresponsive for a second, customers don't distinguish between network and CPU. They just think your site is slow and risky to buy from.

How to tell if you're shipping too much code

Most sites don't need code splitting because it's trendy. They need it because they're paying a tax for code users don't need yet.

Here are the practical signals that code splitting is likely to be a high-ROI fix:

1) Big initial JavaScript for key pages

If your homepage, category page, and product detail page all ship the same giant application bundle, you're probably loading:

- UI for routes the visitor isn't on

- Experiment variants

- Heavy widgets (reviews, recommendations)

- Multiple analytics libraries

- Admin/editor code accidentally included

This is closely related to Unused JavaScript: the more unused JS you deliver at load, the more likely you have splitting opportunities.

2) Slow LCP on mobile, "busy" main thread

A common pattern is:

- LCP is mediocre or poor on mobile

- CPU is pegged early (long tasks)

- Lighthouse flags excessive JS execution

Even if your server is fast (good TTFB), the page can still feel slow because the device is doing too much work.

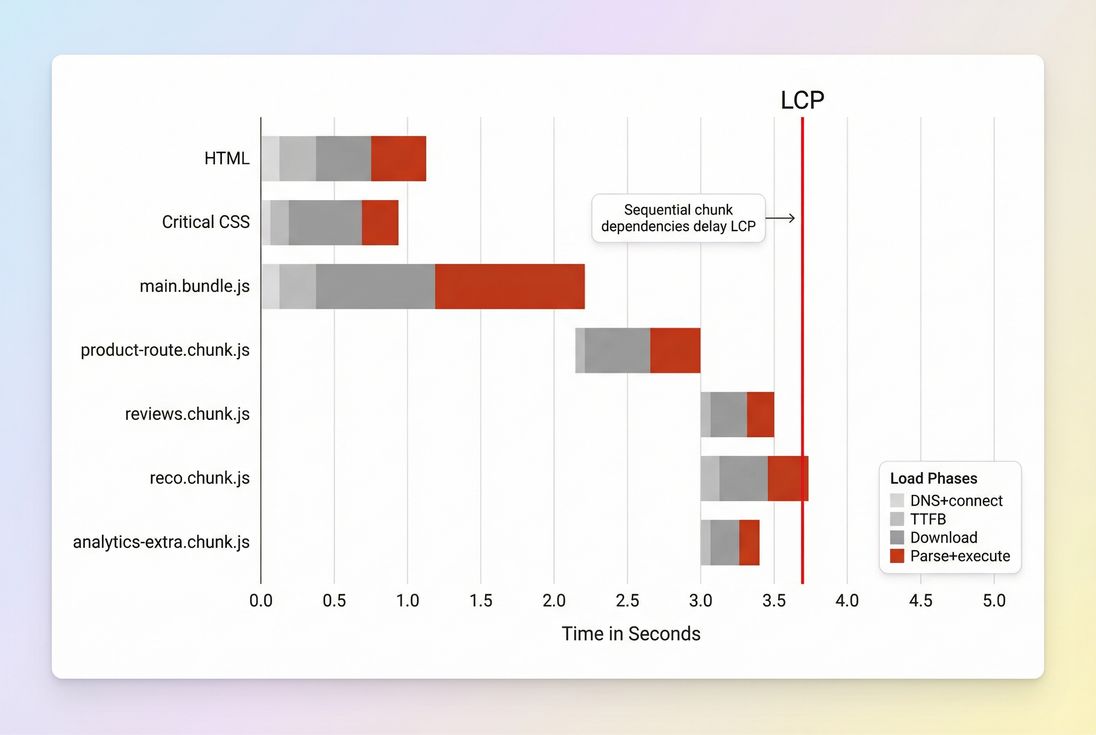

3) Waterfall shows JS delaying rendering

If you inspect a waterfall and see large scripts arriving early and the browser spending time executing them while the page is still blank-ish, code splitting is often part of the fix. (The other common partner is reducing render blocking resources; see Critical rendering path and Render-blocking resources.)

If you use PageVitals, the most direct places to validate this are:

- The Lighthouse tests report: /docs/features/lighthouse-tests/

- The Network request waterfall: /docs/features/network-request-waterfall/

Quick benchmarks that help decision-making

These aren't laws; they're starting points for prioritization:

| Situation you see | What it usually means | Code splitting priority |

|---|---|---|

| Large JS bundles on landing pages | Too much shared code ships everywhere | High |

| Good TTFB but bad LCP | Client-side work is the bottleneck | High |

| INP regresses after adding features | More initialization and long tasks | High |

| Many small script requests and slow start | Over-splitting or poor caching | Medium (fix strategy) |

| Mostly static pages with tiny JS | Not a JS problem | Low |

The Website Owner's perspective: I don't care about "bundle architecture." I care whether the product page loads fast enough to convert paid clicks and whether checkout stays responsive on older iPhones and mid-tier Android phones.

When code splitting helps (and when it backfires)

Code splitting is not automatically a win. It's a trade: less work now vs more coordination later.

It helps most when…

Your site has multiple distinct experiences.

Examples:

- Blog content vs product detail pages

- Logged-out shopping vs logged-in account area

- Checkout vs browse

In these cases, route-based splitting usually removes a lot of dead weight from initial loads.

You have heavy, optional features.

Great candidates:

- Reviews and Q&A modules

- Recommendation carousels

- Product image zoom/gallery enhancements

- Store locator maps

- Chat widgets

- A/B testing SDKs that can be deferred

Your above-the-fold content is simple.

If the first screen is mostly hero image, headline, price, and an add-to-cart button, you can keep that path lean with Above-the-fold optimization plus careful splitting.

It backfires when…

You create a "waterfall of chunks."

This happens when chunk A loads, then triggers loading chunk B, which triggers chunk C. On high-latency networks, multiple sequential requests can be slower than one larger request – especially if you don't use preloading/prefetching well (Preload, Prefetch).

You split too aggressively into tiny files.

Even on HTTP/2 and HTTP/3, requests aren't free. They add:

- Request/response overhead

- Cache lookups

- Scheduling contention

- More places for cache misses

Also, too many tiny chunks can be harder to cache effectively and can increase CPU overhead.

Your caching strategy is weak.

If chunk URLs change every deploy (no stable chunking) or your CDN/browser caching is misconfigured, users will keep re-downloading code. Code splitting works best with strong caching fundamentals:

- Browser caching

- Cache-Control headers

- CDN performance

- Compression like Brotli compression or Gzip compression

Over-splitting can create sequential dependencies. If critical UI code is behind multiple chunk requests, LCP can get worse, not better.

What splitting strategy to use

Website owners don't need ten splitting techniques. You need the two or three that map to real site structure and real revenue pages.

1) Start with route-based splitting

Route-based splitting means each page type gets its own chunk(s):

/homepage chunk/category/*category chunk/product/*product chunk/checkout/*checkout chunk

This is usually the cleanest win because route boundaries align with user intent.

If you run a SPA, this is often implemented with dynamic imports in your router. For example:

// Example: route-based code splitting

const ProductPage = () => import('./routes/product/ProductPage.js')Guardrail: make sure the product route chunk includes what's needed to render the product title/price/image above the fold. Don't put critical product UI behind optional chunks.

2) Split optional widgets by interaction

This is the classic "load when needed" approach.

Examples:

- Load reviews when the reviews section scrolls into view.

- Load zoom/gallery when the user taps a thumbnail.

- Load store locator map only after the user opens the locator.

This pairs well with Lazy loading (for images and iframes) and is often where owners see INP improvements because less code runs during initial input readiness.

3) Separate third-party code from your app

Third-party scripts are frequent performance offenders (Third-party scripts). You often can't "split" them the same way as your bundle, but you can:

- Delay loading nonessential vendors until consent/interaction

- Use

deferappropriately (Async vs defer) - Remove or replace low-value tags

- Load "extra analytics" after the page is stable

Be careful: pushing too much to "after load" can create late long tasks that hurt INP during scroll and tap.

4) Avoid splitting shared foundations too much

Framework/runtime code and shared UI libraries tend to be used everywhere. If you fragment them into many versions or duplicate them across chunks, you can increase total bytes and caching complexity.

A practical approach many teams use:

- One stable "framework/vendor" chunk (cached long-term)

- Per-route chunks for app code

- A few feature chunks for heavy optional features

5) Use preloading/prefetching intentionally

Splitting moves decisions from build time to runtime: "Which chunk should load now?"

Good patterns:

- Preload the chunk you know you'll need for the current route (especially if it's discovered late). See Preload.

- Prefetch likely next-route chunks after the page becomes idle. See Prefetch.

Bad pattern:

- Prefetch everything. That can defeat the whole point by consuming bandwidth and CPU.

The Website Owner's perspective: I want the product page to load fast for first-time visitors, and I also want repeat visitors to feel instant. The right chunking plus caching gives me both – small initial payload and good long-term reuse.

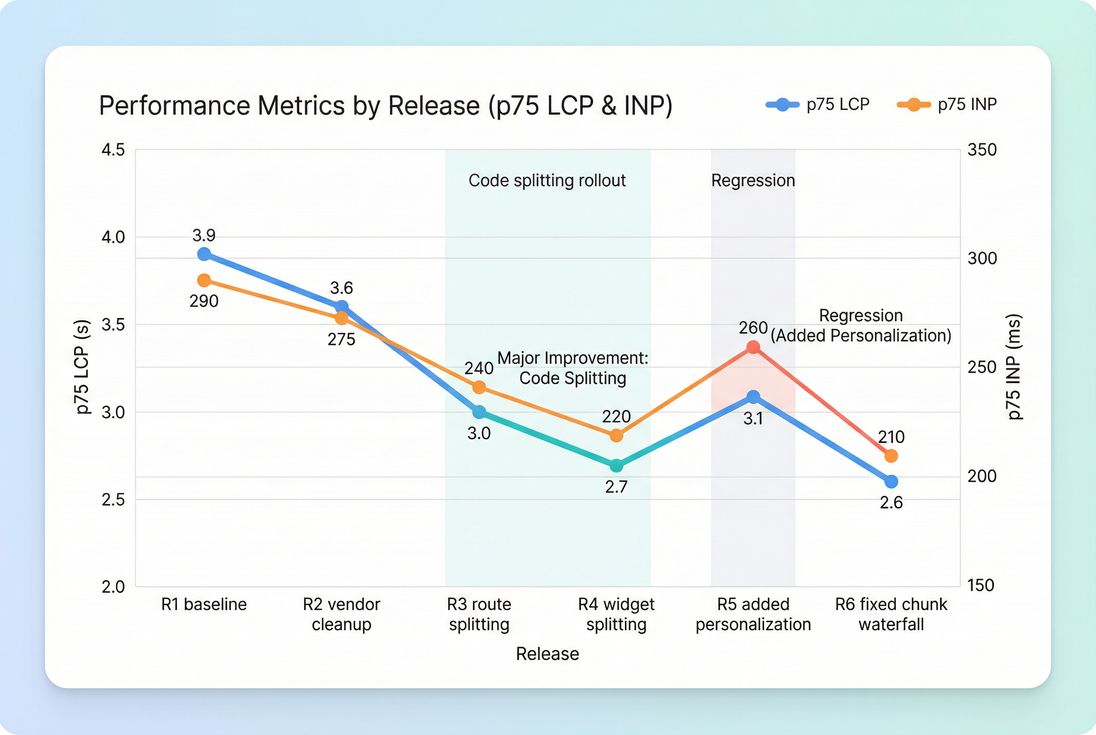

How code splitting shows up in metrics

Code splitting itself isn't a single metric; it changes inputs that your metrics reflect. Here's how to interpret changes without overthinking it.

If LCP improves

Usually you successfully reduced critical path competition:

- Less JS blocking rendering

- Less main thread work before LCP

- Less bandwidth consumed before the LCP resource finishes

Cross-check:

If INP improves

Usually you reduced long tasks and early initialization:

- Fewer heavy libraries booting at startup

- Less JS parsing/execution before user input

Cross-check:

If LCP gets worse after splitting

Common causes:

- Critical UI moved into an async chunk by accident

- Chunk discovery is late (browser can't fetch it early)

- Chunk waterfall (sequential dependencies)

- Network latency dominates and you added extra round trips

Cross-check:

If lab data improves but field data doesn't

Lab tests are controlled; real users aren't. Reasons you may not see field improvement:

- Real traffic has more third-party tags and personalization

- More mid/low-end devices than your lab profile

- Caching differs (repeat visitors vs first-time)

- Country/network mix changes

Cross-check:

A rollout plan that won't break revenue pages

Code splitting failures are usually operational: something loads too late, or a dependency chain appears under real traffic. Roll out like a business change, not just a refactor.

Step 1: Pick two revenue-critical journeys

For e-commerce, common choices:

- Product detail page → add to cart

- Cart → checkout → payment

If you use PageVitals, validate via multistep flows:

- /docs/features/multistep-tests/setting-up-your-first-multistep-test/

- /docs/features/multistep-tests/analyzing-multistep-test-reports/

Step 2: Set a "critical path JS" budget

Budgets keep regressions from creeping back. Even a simple budget like "initial route JS must not exceed last month's baseline" helps. In PageVitals:

- /docs/features/budgets/

Pair this with basics like Asset minification and compression (Brotli compression) so you're not budgeting unoptimized assets.

Step 3: Implement route splitting first

Route splitting is easiest to reason about and easiest to revert. Then move to optional widget splitting.

Step 4: Use the waterfall to spot chunk chains

After a deploy, look specifically for:

- Late discovery of critical chunks

- Sequential chunk loads

- Long parse/execute blocks after chunks download

In PageVitals:

- /docs/features/network-request-waterfall/

Step 5: Validate with both synthetic and field

- Synthetic: catch immediate regressions and verify the critical path got smaller.

- Field: confirm real users saw the improvement (and that it didn't just shift work to later).

If you're tracking Core Web Vitals broadly, keep the framing business-first:

Track code splitting like any other release risk: look for step-changes (R3–R4), regressions (R5), and whether fixes (R6) restore real-user p75 outcomes.

Common mistakes (and quick fixes)

Mistake: "We split, but nothing got faster"

Usually the initial bundle still contains most code (splitting only created more files). Fix by:

- Splitting at route boundaries

- Removing dead code (Unused JavaScript)

- Reducing shared dependencies

- Auditing third-party scripts

Mistake: "We improved LCP but checkout feels laggy"

You may have deferred too much and now load heavy chunks right when users interact. Fix by:

- Keeping checkout-critical code warm (preload when cart opens)

- Avoiding late initialization spikes

- Measuring INP and long tasks during checkout steps

Mistake: "Chunking exploded our request count"

Fix by:

- Merging tiny chunks that always load together

- Ensuring HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 is enabled (HTTP/2 performance, HTTP/3 performance)

- Improving caching and CDN delivery (CDN performance)

The decision rule website owners can use

If your key pages are slow and JavaScript-heavy, code splitting is one of the most reliable ways to buy back time – because it reduces both network cost and CPU cost on the critical path.

Use this simple decision rule:

- If users need it to see and start, keep it in the critical path.

- If users need it only after they engage, split it and load it deliberately.

- If it exists only for edge cases, split it and consider removing it entirely.

That's how code splitting turns from a developer tactic into a business lever: you stop paying the performance cost of features that aren't helping conversion right now.

Frequently asked questions

Look for a large initial JavaScript payload, slow LCP, or sluggish interactions on mobile. If your homepage or product pages ship features customers do not use immediately, splitting usually helps. Validate with Lighthouse lab runs plus field data trends so you do not optimize only for tests.

Good code splitting reduces work on the critical path: fewer bytes to download, parse, and execute before the above the fold can render. That often improves LCP. Poor splitting can create a chunk waterfall that delays critical UI code, making LCP worse even if total bytes are smaller.

There is no universal number, but as a practical rule: keep initial route JavaScript as small as your experience allows on mobile. Many commerce sites struggle when they ship several hundred kilobytes compressed plus heavy execution. Your best benchmark is your own conversion funnel and Core Web Vitals p75.

Yes. Too many tiny chunks can increase round trips and create request waterfalls, especially on high latency mobile networks. It can also reduce cache efficiency if chunk names change frequently or if shared code is duplicated across chunks. The goal is fewer critical bytes without adding fragile loading behavior.

Start with route based splitting, then split obvious non critical features such as reviews, recommendations, chat widgets, and admin tools. Measure before and after with synthetic tests and a multistep checkout flow. Set a JavaScript performance budget so changes do not creep back in over time.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial