Table of contents

Gzip compression explained

Every extra megabyte you send is paid for twice: once in bandwidth and once in lost patience. On mobile networks, uncompressed HTML, CSS, and JavaScript can easily add seconds to load time – enough to reduce conversion rates, increase bounce, and make paid traffic less efficient.

Gzip compression is a server-side (or CDN-side) way to shrink text-based responses – like HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and JSON – before sending them over the network. The browser automatically decompresses them. When it's working, users download fewer bytes for the same page.

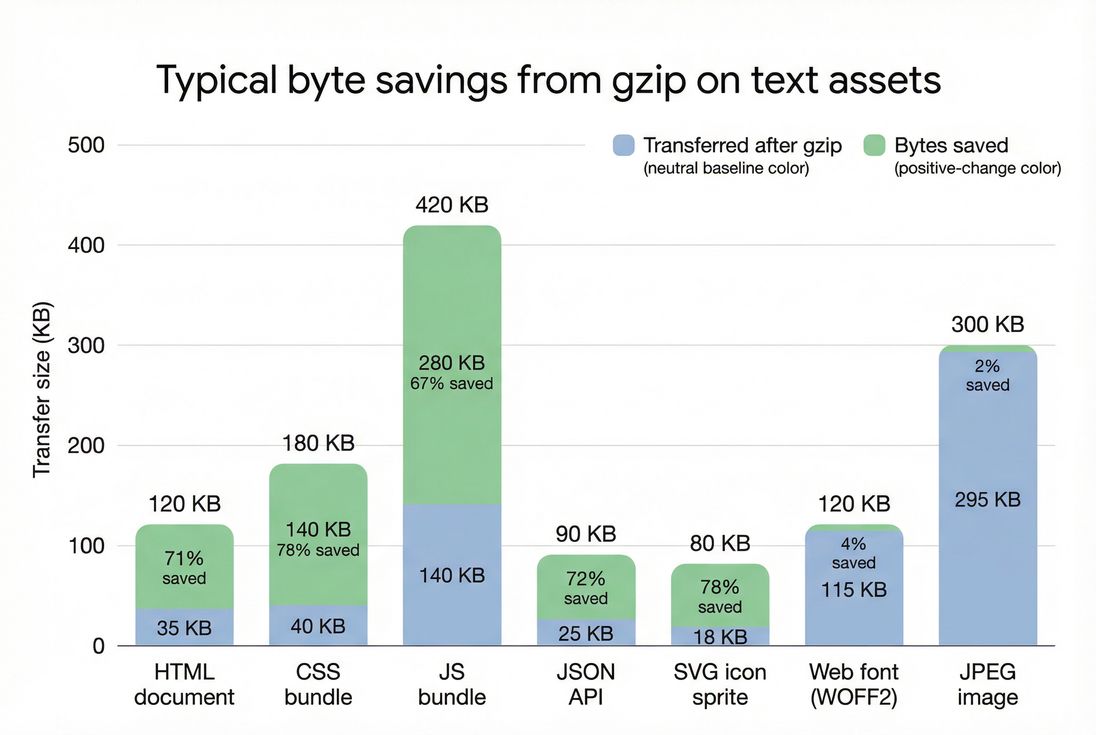

Gzip meaningfully reduces transfer size for text assets (HTML/CSS/JS/JSON/SVG) but does almost nothing for already-compressed formats like JPEG and WOFF2.

What gzip reveals about page speed

Gzip isn't a "score" so much as a binary capability with measurable impact: are you sending compressible resources in a compressed form, and how many bytes are you saving?

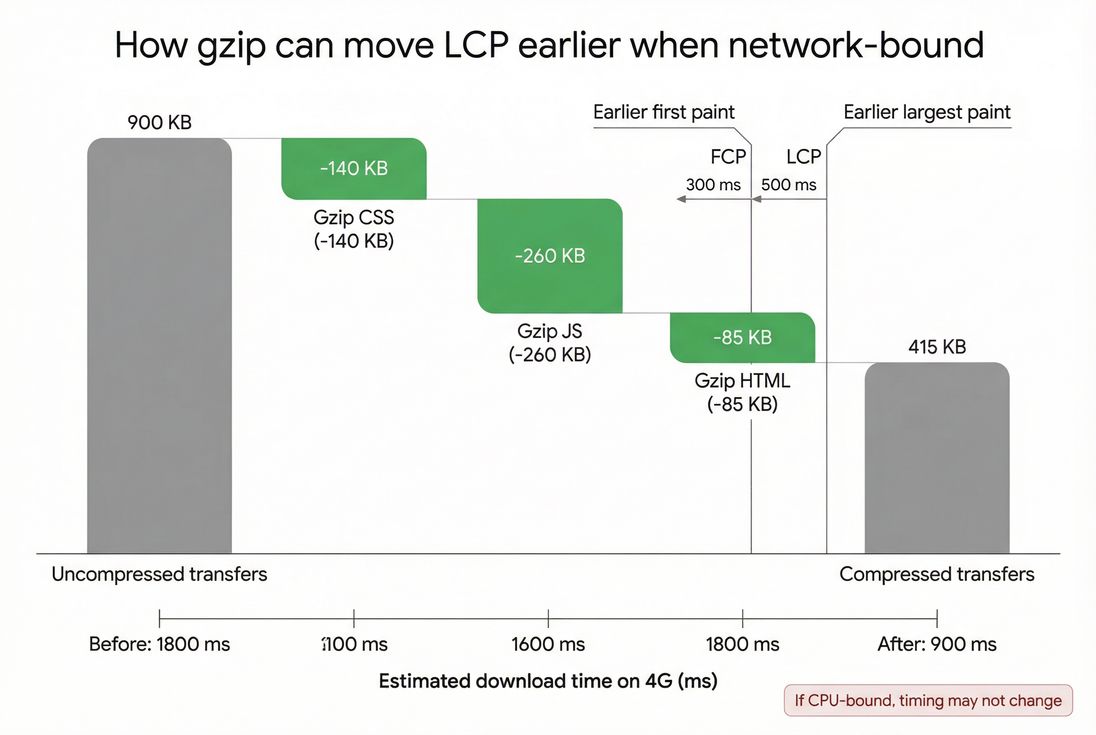

From a speed perspective, gzip primarily affects:

- Download time for render-critical files (often CSS and sometimes JS), which can impact FCP and LCP when the bottleneck is network transfer.

- Total page weight, which affects repeat user experience and low-end devices, and supports a sustainable performance budget.

- Bandwidth costs for both you and your users.

Gzip usually does not fix problems dominated by:

- High TTFB (server slowness)

- Heavy JS execution time or long tasks

- Layout instability (CLS) issues

The Website Owner's perspective: If gzip isn't enabled, you're paying to ship bloated text files to every visitor. It's one of the few optimizations that can reduce load time without redesigning anything – so it's a straightforward "stop the bleeding" fix before deeper work like code splitting or critical CSS.

How gzip works in real requests

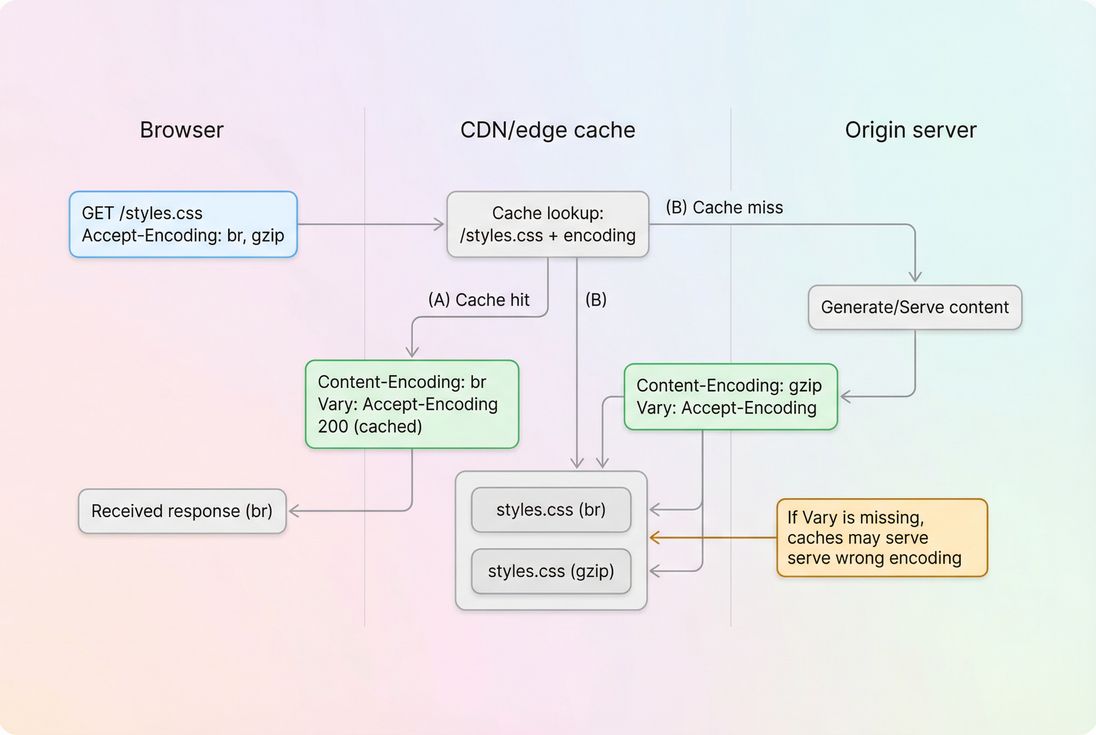

Gzip works through standard HTTP content negotiation. In plain terms:

- Browser asks: "Do you have a compressed version?"

It sendsAccept-Encoding: gzip, br(exact values vary). - Server/CDN responds with either:

- A compressed payload and

Content-Encoding: gzip, or - An uncompressed payload (no

Content-Encoding, sometimes calledidentity)

- A compressed payload and

- Correct caching requires acknowledging that the response can vary based on encoding.

The headers that matter most:

Accept-Encoding(request): what the client supportsContent-Encoding: gzip(response): what you actually usedVary: Accept-Encoding(response): tells caches there are multiple variants

If you use a CDN, the best practice is typically:

- CDN compresses at the edge (fast, consistent, offloads origin CPU)

- Origin sends clean, cacheable content with correct

Content-Typeand caching headers (see Cache-Control headers)

Compression is negotiated per request. Correct caching depends on treating "br" and "gzip" as separate variants and returning Vary: Accept-Encoding.

What "calculation" means for gzip

You'll usually see gzip impact expressed as:

- Transferred size vs resource size (in browser DevTools)

- Bytes saved (opportunity reporting)

- Compression ratio / percent reduction (varies by tool)

Practically, you care about: how many fewer kilobytes are sent over the network for the resources that matter to rendering.

A common pattern in DevTools is:

- "Size" shows something like

35 KB / 120 KB

This typically means 35 KB transferred, 120 KB uncompressed (exact display varies by browser).

What influences gzip results

File type and content

Gzip is best for repetitive text. It performs well on:

- HTML

- CSS

- JavaScript

- JSON

- SVG (as text)

It performs poorly (or is pointless) for already compressed / entropy-heavy formats:

- JPEG/PNG/WebP/AVIF images (see Image compression and WebP vs AVIF)

- MP4/WebM video

- PDF (often already compressed)

- WOFF2 fonts (already compressed)

If your setup gzips everything indiscriminately, you may burn CPU for near-zero gain.

Minification changes the "shape" of text

Minification (see Asset minification) usually makes files smaller – but it can slightly reduce how much gzip can compress because it removes whitespace and repetition patterns.

In practice:

- Minify first, then compress is still correct.

- You should expect gzip savings to remain strong on CSS/JS even after minification.

- If gzip savings collapse, it's often because the file isn't being gzipped at all (misconfiguration), or because the file includes lots of already-compressed blobs (like big base64 strings).

Compression level vs CPU cost

Gzip has "levels" (implementation-specific, often 1–9). Higher levels compress smaller, but require more CPU time.

For website owners, the main takeaway:

- If gzip is handled by your CDN, CPU cost is rarely your concern.

- If gzip is done by your origin, overly aggressive settings can increase server work and harm server response time and TTFB under load.

Caching and reuse

Compression helps most when:

- The file is not already cached by the browser (first visit, new version)

- The user is on a constrained network (high latency, low throughput)

To multiply the benefit:

- Use strong browser caching for versioned static assets (see Browser caching and Cache TTL)

- Ensure your deploy process fingerprints assets so you can safely cache them long-term

The Website Owner's perspective: Compression reduces the cost of each visit, but caching reduces how often you pay it. If you're spending on acquisition, you want both: compressed first loads and aggressively cached repeat loads.

When gzip breaks (and how to spot it)

"Enable text compression" but you think it's on

This usually means some responses are still uncompressed, often:

- HTML documents (common in frameworks where static assets are handled correctly but HTML routes aren't)

- JSON API responses

- CSS/JS served from a different domain/subdomain

- Third-party assets (you can't fix those, but you can factor them into vendor decisions)

A waterfall view makes this visible immediately. If you're using PageVitals, the Network Request Waterfall is the right place to confirm per-request headers and transfer sizes: /docs/features/network-request-waterfall/

Missing Vary: Accept-Encoding

If Vary is missing, an intermediary cache can store one encoding and serve it to clients that didn't ask for it.

Real-world symptom:

- Some users get garbled content or downloads that fail (rarer today, but still possible with misconfigured proxies).

- Or you get inconsistent results across test locations/agents.

Double compression or incorrect content encoding

Misconfigured setups sometimes:

- Compress at origin and then compress again at CDN (usually prevented, but it happens)

- Set

Content-Encoding: gzipwithout actually gzipping (browser tries to decompress garbage)

If you see broken styling/scripts only in production (not local), check:

- Response headers at the edge

- Whether the payload is truly compressed

Compressing too-small files

For tiny files, gzip headers can outweigh the savings. Many servers have a minimum size threshold (for example, only compress responses larger than ~1 KB).

This is normal. Don't chase 100% coverage if the "misses" are tiny.

How much gzip should you aim for

Think in terms of coverage and impact, not perfection.

Practical benchmarks

| Asset type | Should be compressed? | Typical savings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTML | Yes | High | Often forgotten on dynamic routes |

| CSS | Yes | Very high | Frequently render-critical |

| JavaScript | Yes | High | Can be huge; big savings |

| JSON | Yes | High | Especially on search/autocomplete APIs |

| SVG | Yes | High | SVG as text compresses well |

| Images (JPEG/PNG/WebP/AVIF) | No | Low | Already compressed |

| Fonts (WOFF2) | Usually no | Low | WOFF2 is already compressed |

Decision rule for busy teams

Prioritize enabling compression for:

- Your HTML document(s) (home page, category page, product page)

- Render-critical CSS

- Large JS bundles

- High-traffic JSON endpoints

Then validate that your caching strategy is sound (see Cache-Control headers and Edge caching).

How gzip affects Core Web Vitals

Compression reduces bytes, which reduces download time. That can improve:

- LCP, when the LCP element is delayed by network transfer of CSS/JS/HTML (common on mobile)

- FCP, similarly, if CSS/HTML delivery is the bottleneck

Compression usually does not directly improve:

- INP (Interaction to Next Paint), unless smaller JS means less script to download before interactivity (indirect, depends on architecture)

- CLS, because layout shift is mostly about reserving space and late-loading content

To reason about it:

- If your bottleneck is network + bytes, compression is high leverage.

- If your bottleneck is CPU + main thread, focus on unused JavaScript, main thread work, and third-party scripts.

When a page is network-bound, gzip's byte savings can translate into faster downloads and earlier paint milestones, especially for CSS and large JS bundles.

How to enable gzip safely

Where you enable it depends on your stack. The safest general approach:

- Prefer edge compression (CDN)

- Ensure correct headers (

Content-Encoding,Vary) - Exclude already-compressed formats

- Use a sane minimum size threshold

- Avoid extreme compression levels on origin

CDN-first setup (recommended)

Most CDNs can compress automatically for the right MIME types. The key operational point is: verify what's happening at the edge, not just at origin.

Pair this with:

- Strong caching rules (CDN performance, CDN vs origin latency)

- Correct

Cache-Controlfor static assets (Browser caching)

Origin compression (common on VPSs)

If you compress at origin (Nginx/Apache/Node/etc.):

- Compress only text MIME types (

text/html,text/css,application/javascript,application/json,image/svg+xml) - Set

Vary: Accept-Encoding - Use moderate settings to avoid CPU spikes

If you're optimizing for stability under load, it's often better to:

- Precompress static assets during build (

.gzfiles) and serve them when supported - Or shift compression responsibility to the CDN

Don't confuse gzip with other optimizations

Gzip is not a substitute for:

- Reducing JS payloads (JS bundle size, Unused JavaScript)

- Loading scripts responsibly (Async vs defer)

- Fixing render-blocking (Render-blocking resources)

- Optimizing images (Image optimization)

It's a baseline requirement – then you move up the stack.

How to verify gzip (fast checks)

Browser DevTools

In Chrome DevTools → Network:

- Add the Content-Encoding column (or click a request → Headers)

- Confirm

content-encoding: gzipfor HTML/CSS/JS - Compare Transferred vs Resource sizes

Command line (quick and reliable)

Use curl to check headers (example pattern):

- Request with gzip support, verify

Content-Encoding: gzip - Confirm

Vary: Accept-Encodingis present on compressible content

Synthetic testing and ongoing monitoring

If you run Lighthouse tests, gzip gaps often show up as a text compression opportunity. If you need help interpreting those audits over time, PageVitals' Lighthouse reporting can capture and compare results across runs: /docs/features/lighthouse-tests/

The Website Owner's perspective: The "win" isn't just enabling gzip once. The win is keeping it enabled through redesigns, CDN changes, new frameworks, and new subdomains. Add it to your release checklist so a deploy can't quietly switch your HTML back to uncompressed.

Gzip vs Brotli in plain terms

Gzip is widely supported and effective. Brotli is typically better for modern browsers.

Use this rule:

- Serve Brotli where supported (usually over HTTPS).

- Serve gzip as fallback.

- Never serve uncompressed text unless there's a very specific reason.

If you want a deeper comparison and guidance, see Brotli compression.

A simple action plan

If you want the practical checklist without overthinking it:

- Check your top 10 pages (homepage, category, product, cart, checkout steps) for

Content-Encodingon HTML, CSS, JS. - Fix HTML compression first (most common miss, highest leverage).

- Verify

Vary: Accept-Encodingon compressed responses. - Exclude images and fonts from gzip rules.

- Confirm caching strategy so you're not re-downloading the same assets every page view (see Browser caching and Cache-Control headers).

- Re-test and watch TTFB to ensure origin CPU isn't the new bottleneck (see TTFB).

Done well, gzip is one of the lowest-effort ways to reduce transfer size and protect your Core Web Vitals from "death by a thousand kilobytes."

Frequently asked questions

Yes. HTTP/2 reduces connection overhead, but it does not reduce file size. Gzip directly cuts transferred bytes for HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, which shortens download time on mobile and slow networks. CDNs usually make it easier to enable compression consistently at the edge.

For text assets, a strong outcome is typically a 60 to 80 percent reduction in transferred bytes versus the uncompressed size. If you see minimal savings, the file may already be compressed, minified very heavily, or mostly random-like content such as inline base64 blobs.

It can if your origin server compresses responses on the fly with an aggressive compression level, especially for large HTML or JSON under CPU load. The fix is usually to use a moderate gzip level, precompress static files, or let your CDN handle compression at the edge.

Lighthouse flags specific responses that are still being sent uncompressed or with the wrong headers. Common causes include missing compression on HTML routes, a proxy stripping Content-Encoding, incorrect MIME type detection, or cached uncompressed variants. Check the exact request headers and response headers in a waterfall.

Prefer Brotli for modern browsers over HTTPS because it usually compresses smaller than gzip for CSS and JavaScript. Keep gzip as a fallback for older clients. The practical goal is that every compressible text response returns either br or gzip, not identity, and that caching handles variants correctly.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial