Table of contents

TLS handshake performance

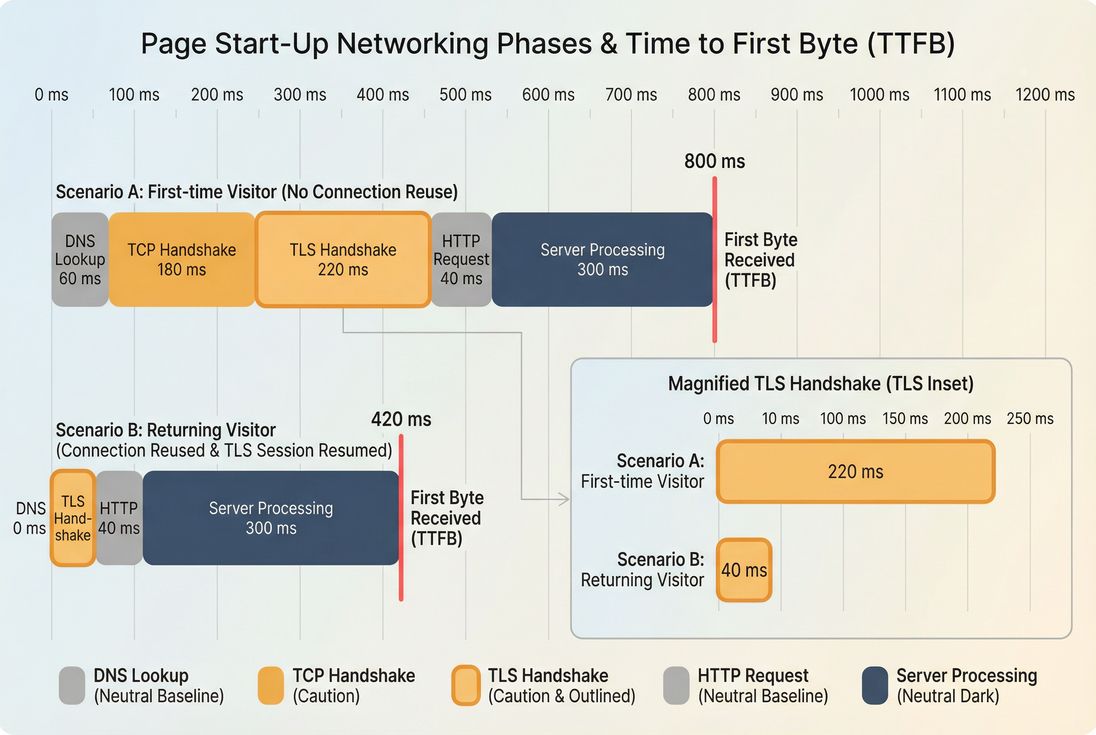

TLS handshake performance is one of those "invisible" delays that can quietly tax every first-time visitor – especially on mobile and for shoppers arriving from ads. When it's slow, it pushes out your first byte, delays rendering, and can drag down conversion rates and Core Web Vitals without any obvious "big asset" to blame.

In plain English: TLS handshake performance is how long it takes a browser and server to complete the cryptographic setup needed for HTTPS before any real content can be delivered. It happens after DNS and TCP, and before the browser can securely request HTML, CSS, JS, images, or APIs.

If you want the short mental model: a slow handshake is usually a latency problem (distance + mobile networks) multiplied by "how many new connections you force the browser to make."

What TLS handshake performance reveals

TLS handshake time is a network-and-connection efficiency signal. It tells you:

- How expensive it is for a user to "start talking securely" to your site (or any third-party origin you call).

- Whether you're benefiting from connection reuse and session resumption, or repeatedly paying full handshake costs.

- Whether latency (RTT), packet loss, or edge routing is becoming the dominant limiter for first-time visits.

TLS handshake is not a Core Web Vital by itself, but it directly impacts metrics you care about:

- TTFB (because TLS must complete before the request can be made): see /academy/time-to-first-byte/

- FCP/LCP (because late HTML and render-blocking resources push rendering out): see /academy/first-contentful-paint/ and /academy/largest-contentful-paint/

- The "feel" of speed on mobile, where network latency dominates: see /academy/mobile-page-speed/

The Website Owner's perspective

If TLS handshake time goes up, you may see "we didn't change anything" slowdowns: ads underperform, bounce rate rises, and LCP regresses – especially for new visitors. The fix is rarely "optimize images"; it's usually about fewer new connections, better routing to nearby edges, and modern TLS behavior.

When TLS handshake time becomes a problem

A single TLS handshake is often "fine." The problem is how often you trigger it and where users are when it happens.

Practical benchmarks (use percentiles)

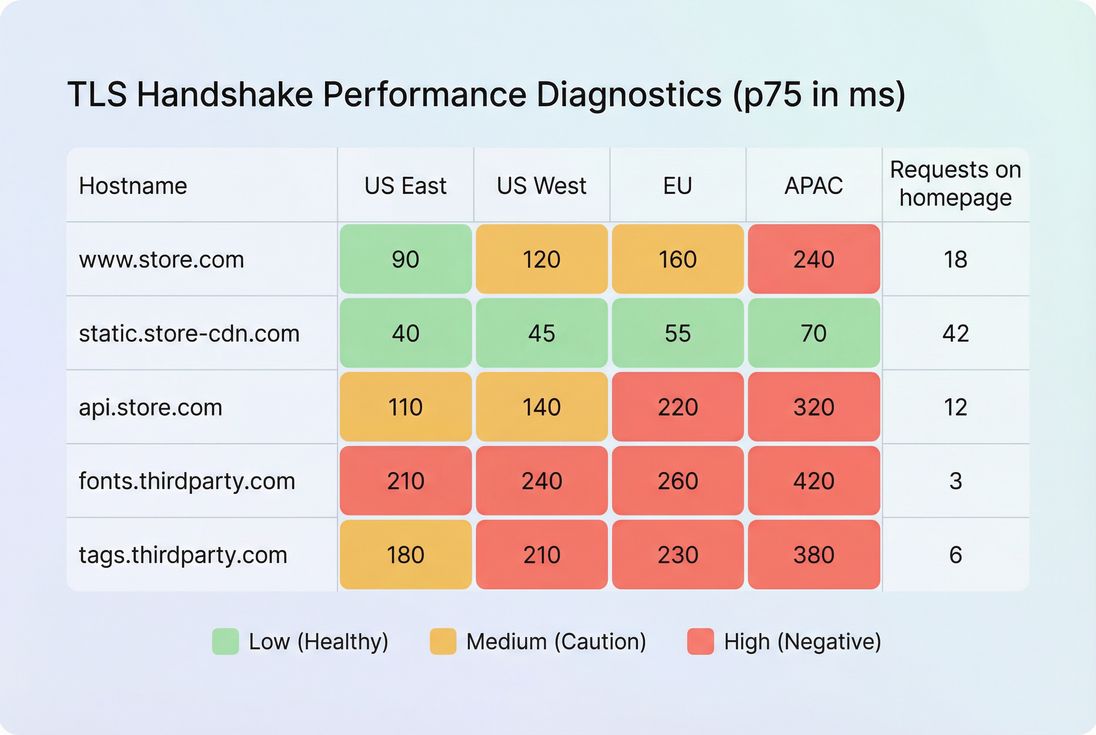

Handshake time varies with geography and connection quality, so avoid one-size-fits-all targets. Use this table as a decision aid for typical consumer traffic:

| TLS handshake (p75) | Interpretation | What it usually means |

|---|---|---|

| < 100 ms | Strong | Close edge, low RTT, TLS 1.3, good reuse/resumption |

| 100–200 ms | Normal | Mobile latency or moderate distance; still acceptable |

| 200–400 ms | Concerning | Users far from edge, poor reuse, extra third-party origins |

| > 400 ms | Likely hurting | High RTT/packet loss, full handshakes frequently, routing issues |

Two "gotchas" to keep in mind:

- TLS time compounds across origins. If your page calls 15 third-party domains, you might pay 15 separate DNS+TCP+TLS setups (unless connections are reused or already warm).

- First page view is where it hurts. Returning navigation often reuses existing connections (see /academy/connection-reuse/), so handshake problems can hide in averages.

Symptoms that usually implicate TLS

- TTFB is high but server processing is stable (see /academy/server-response-time/).

- Waterfalls show big "secure connection" phases before HTML, fonts, or critical JS.

- Slowdowns are worse on mobile and for distant geographies (see /academy/network-latency/).

What drives TLS handshake time

TLS handshake duration is mainly determined by round trips and crypto work, plus a few "paper cuts" that show up at scale.

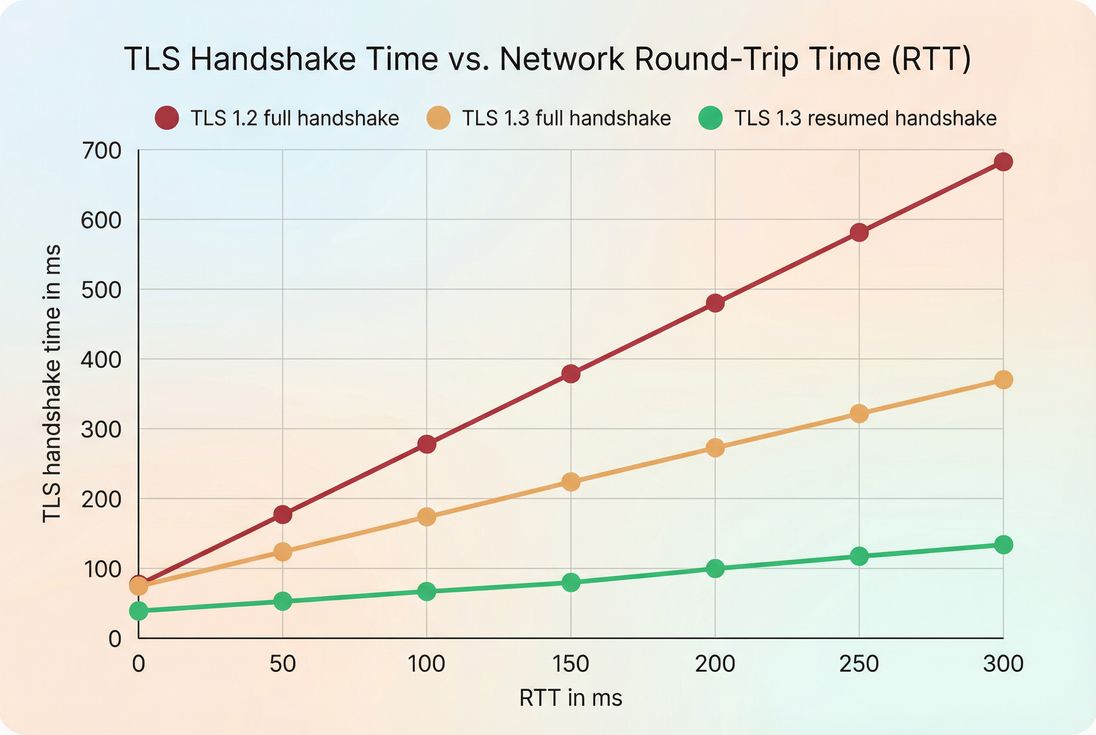

1) Network latency (RTT)

TLS handshakes require at least one network round trip after the TCP connection is established. So if your users have high RTT, your handshake will be slower even with perfect server config.

If you're analyzing alongside RTT, use it as a reality check. PageVitals documents how RTT is measured here: /docs/metrics/round-trip-time/.

Related concepts:

- DNS can add more latency before TLS even starts: /academy/dns-lookup-time/

- TCP setup is its own cost: /academy/tcp-handshake/

- TLS is then layered on top: /academy/tls-handshake/

2) TLS version and handshake mode

- TLS 1.3 generally reduces handshake overhead versus TLS 1.2.

- Session resumption can cut handshake time dramatically for returning visitors.

- 0-RTT (TLS 1.3 early data) can help in limited cases, but it's not universally applicable and has replay considerations.

A common real-world pattern:

- First-time visitor: full handshake (expensive)

- Returning visitor: resumed handshake (cheap), especially if connection is reused

3) Certificate chain and validation behavior

Even if RTT is stable, TLS can be slowed by:

- Large certificate chains (more bytes to send before finishing)

- Missing or misconfigured intermediates

- Lack of OCSP stapling, causing extra validation work or delays

- Frequent certificate changes that reduce resumption effectiveness

This tends to show up as "TLS is slow even when users are close to the edge."

4) Server/edge CPU and TLS termination path

TLS involves cryptography. If TLS is terminated on:

- A busy origin server

- An overloaded WAF layer

- A region far from the user

…then handshake time rises. This is where CDN architecture and edge placement matter (see /academy/cdn-performance/ and /academy/cdn-vs-origin-latency/).

5) Too many hostnames (especially third parties)

Every unique origin can trigger a new connection setup. Common culprits:

- Tag managers and ad pixels

- A/B testing tools

- Chat widgets

- Multiple analytics endpoints

- Fonts from third-party domains

This is why TLS handshake is closely tied to third-party governance (see /academy/third-party-scripts/).

The Website Owner's perspective

If you're paying for traffic, every extra third-party origin is like adding a "toll booth" before the page can fully start. Even if each handshake is only 150–250 ms, the critical path can end up waiting on the slowest domain – often one you don't control.

How it's measured and calculated

TLS handshake timing is typically derived from browser performance timing events. In Chrome and other modern browsers, navigation and resource timing include:

- When the connection starts

- When the secure handshake starts

- When the connection ends (ready to send request)

TLS handshake time is the elapsed time between the secure-connection start and the connection end. If secureConnectionStart is missing (or 0), the request may be non-secure, reused, or timing may be unavailable.

This matters operationally because:

- A request can show 0 ms TLS when it reuses an existing connection (great).

- You should compare like-for-like: first navigation vs repeat, cold cache vs warm cache, same geography.

If you're using a waterfall view, TLS is typically shown as a "secure connection" segment in the request bar. PageVitals documents reading request timing in the waterfall here: /docs/features/network-request-waterfall/.

Lab vs field interpretation

Use both, for different decisions:

- Lab/synthetic testing is great to reproduce and isolate the issue (fixed device/network profile). See /academy/field-data-vs-lab-data/

- Field/RUM reveals where it really hurts (mobile users, specific ISPs, certain geos). See /academy/real-user-monitoring/

A common workflow:

- Field data shows p75 handshake jumped for mobile users in a region.

- Synthetic tests from that region confirm the issue and show which hostnames are slow.

- You decide whether to change routing/CDN/WAF, reduce third parties, or adjust resource loading.

How to diagnose and act on changes

When TLS handshake time changes, the key is to answer two questions quickly:

- Did RTT change (network reality), or did our architecture change (we caused it)?

- Is it one hostname, or many?

Step 1: Break it down by hostname

Look for patterns like:

- Only

www.example.comis slower → edge/origin/WAF path issue - Only

static.examplecdn.comis slower → CDN POP/routing/config - Only third-party domains are slower → vendor/network issue or too many vendors

This is where third-party audits pay off: fewer origins means fewer new handshakes.

Step 2: Decide if it's "one-time" or "every time"

If the handshake is slow only on cold loads, you can often mitigate with connection reuse and early connection warming.

If it's slow even for returning navigation, suspect:

- short keep-alive/idle timeouts (connections closing too quickly)

- frequent hostname sharding (assets spread across many domains)

- intermediaries (WAF/proxy) that prevent reuse or resumption

Related reading: /academy/connection-reuse/ and /academy/http2-performance/.

Step 3: Tie it back to business-critical pages

Handshake matters most when it blocks:

- HTML document request (TTFB)

- render-blocking CSS (see /academy/render-blocking-resources/)

- LCP resource discovery (see /academy/critical-rendering-path/)

If the slowest handshake is for a late-loading marketing tag, it may not be worth heavy engineering effort. If it's your HTML or critical CSS host, it's urgent.

The Website Owner's perspective

Don't chase "perfect" TLS numbers everywhere. Prioritize the connections that block revenue: landing pages from paid campaigns, category pages, product pages, and checkout. If handshake improvements reduce TTFB on these pages, you usually see downstream gains in LCP and conversion.

How to improve TLS handshake performance

Most wins come from reducing how often handshakes occur and ensuring the handshake you do perform is modern and close to users.

1) Reduce cross-origin dependencies

This is the most underappreciated TLS lever.

- Consolidate vendors where possible (fewer domains)

- Self-host critical assets when it's realistic (fonts, small libraries)

- Remove or defer non-essential third-party scripts (see /academy/third-party-scripts/)

If you must keep third parties, keep them off the critical path:

- Load non-critical scripts with /academy/async-vs-defer/

- Delay tags until after meaningful render where appropriate

2) Use preconnect selectively

A well-placed preconnect can start DNS+TCP+TLS earlier, so the handshake finishes before the browser truly needs the resource.

Use it for:

- your primary CDN asset domain

- a critical font origin (if not self-hosted)

- a required payment or identity provider used very early

Learn the mechanics here: /academy/preconnect/

Avoid:

- preconnecting to every third party "just in case"

- preconnect for resources that are already late or not critical

3) Ensure modern TLS and resumption support

Work with your host/CDN/WAF to confirm:

- TLS 1.3 is enabled

- session tickets/resumption are working

- OCSP stapling is enabled (where applicable)

- certificate chain is correct and minimal

These are configuration-level improvements that can yield immediate handshake reductions without code changes.

4) Improve edge proximity and routing

If RTT is the main driver, your biggest lever is "make the handshake happen closer to the user":

- Put HTML behind a CDN where possible (see /academy/edge-caching/)

- Confirm traffic is actually routed to the nearest POP

- Compare edge vs origin contribution (see /academy/cdn-vs-origin-latency/)

5) Increase connection reuse

Connection reuse reduces how often you pay for TLS:

- Prefer HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 where possible (see /academy/http3-performance/)

- Avoid unnecessary domain sharding

- Use long-lived connections wisely (balanced with resource constraints)

This can be especially impactful on pages that load many same-origin assets.

6) Don't confuse TLS fixes with payload fixes

TLS handshake optimization helps starting the delivery. If you're still slow after that, you likely need payload and rendering work:

- /academy/asset-minification/

- /academy/code-splitting/

- /academy/critical-css/

- /academy/image-optimization/

A good diagnostic pattern is:

- If TLS + TTFB are the problem, start with network/edge/connection strategy.

- If TTFB is fine but LCP is slow, shift to rendering and resource prioritization (see /academy/above-the-fold-content/).

A practical decision checklist

Use this as a quick "what do I do next?" guide:

Is TLS handshake high for your HTML origin?

Prioritize edge proximity, TLS 1.3, resumption, WAF/CDN routing.Is TLS handshake high mainly for third parties?

Reduce vendors, defer non-critical tags, and limit critical-path cross-origin calls.Is TLS high only on first visits?

Improve reuse/resumption and use selective preconnect for truly critical origins.Does TLS track RTT by geography?

Treat it as a network placement problem: move the handshake closer to users and reduce the number of handshakes per page.

If you need a single "north star" metric relationship to watch: when TLS handshake time falls, TTFB usually falls (assuming server work is unchanged). For TTFB measurement details, see /docs/metrics/time-to-first-byte/.

Frequently asked questions

As a practical target, aim for p75 TLS handshake under 100 ms on desktop-heavy traffic and under 200 ms for mobile-heavy traffic. Higher numbers often indicate high network latency, lack of connection reuse, or too many third-party origins. Focus on p75/p95, not just averages.

A spike usually means traffic is no longer hitting a nearby edge, the WAF is adding extra latency, or new domains were introduced (more handshakes). Confirm which hostname increased, compare edge versus origin routing, and check whether TLS 1.3 and session resumption are enabled on the new path.

Yes, because TLS happens before the first byte of HTML or key assets can arrive. Reducing handshake time typically reduces TTFB, which often improves LCP on content-heavy and server-rendered pages. It is rarely the only lever, but it is a clean win when latency or third-party origins are the real bottleneck.

Use preconnect selectively for truly critical cross-origin requests needed early in the load, such as your CDN asset host or a required font host. It can hide handshake latency by starting DNS, TCP, and TLS sooner. Overusing it can waste connections, increase contention on mobile, and reduce real gains.

If TLS time tracks round-trip time and varies strongly by geography or mobile networks, latency is likely the driver. If TLS is high even near your edge, suspect configuration: TLS 1.2-only, missing session resumption, certificate chain issues, or CPU constraints on edge/origin. Use waterfalls plus field percentiles to confirm.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial