Table of contents

Cache-Control headers explained

Slow sites don't just lose impatient first-time visitors – they quietly bleed revenue from returning customers who should be flying through category pages, product pages, and checkout. When repeat visits still feel "cold," the usual culprit is simple: the browser is being forced to re-download files it already has.

Cache-Control is an HTTP response header that tells browsers and CDNs if they can store a resource, and for how long they can reuse it without re-checking the server. It's one of the highest-ROI page speed levers because it cuts network requests, bytes transferred, and backend load – especially on mobile connections.

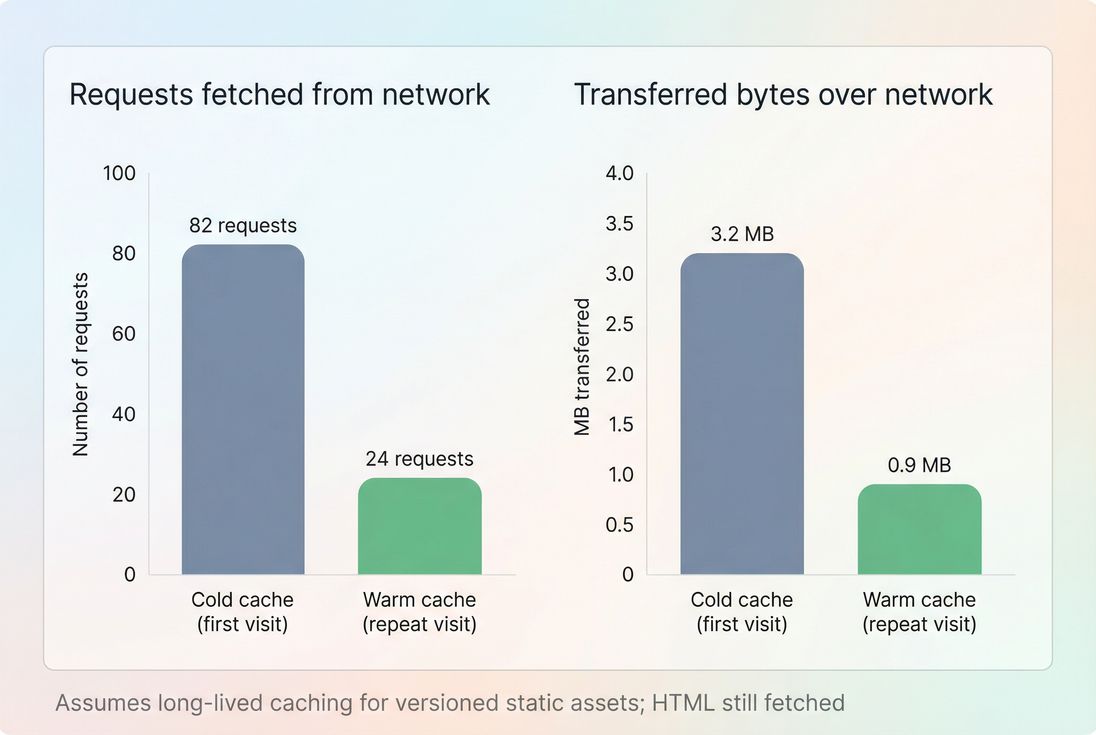

Good Cache-Control policies mainly pay off on repeat views: fewer requests and fewer bytes over the network.

What Cache-Control controls

Cache-Control is not a "speed metric" by itself. It's a policy that directly influences speed outcomes:

- Repeat-visit load time: reused CSS/JS/images means fewer downloads and faster rendering.

- TTFB under load: fewer requests reaching origin reduces backend pressure (see TTFB and server response time).

- CDN effectiveness: shared caching is usually governed by

s-maxageand related behavior (see CDN performance and edge caching). - Core Web Vitals: caching rarely fixes LCP for first-time visitors, but it can noticeably improve LCP for returning users and reduce variability (see LCP and Core Web Vitals).

The Website Owner's perspective

If your acquisition spend brings users back (email, SMS, retargeting, loyalty), but "returning" sessions aren't faster than "new" sessions, you're paying for traffic that behaves like a first visit. Cache-Control is how you stop re-buying the same downloads.

Browser caching vs CDN caching

Cache-Control applies to multiple caches:

- Browser cache (private): the user's device stores resources for reuse.

- Shared caches (CDN/edge): a cache shared across users, typically for anonymous traffic.

That distinction matters because some directives are designed specifically for shared caches (s-maxage), and some are meant to prevent shared caching (private).

If you want the basics first, start with browser caching and then come back here.

How browsers decide to reuse a file

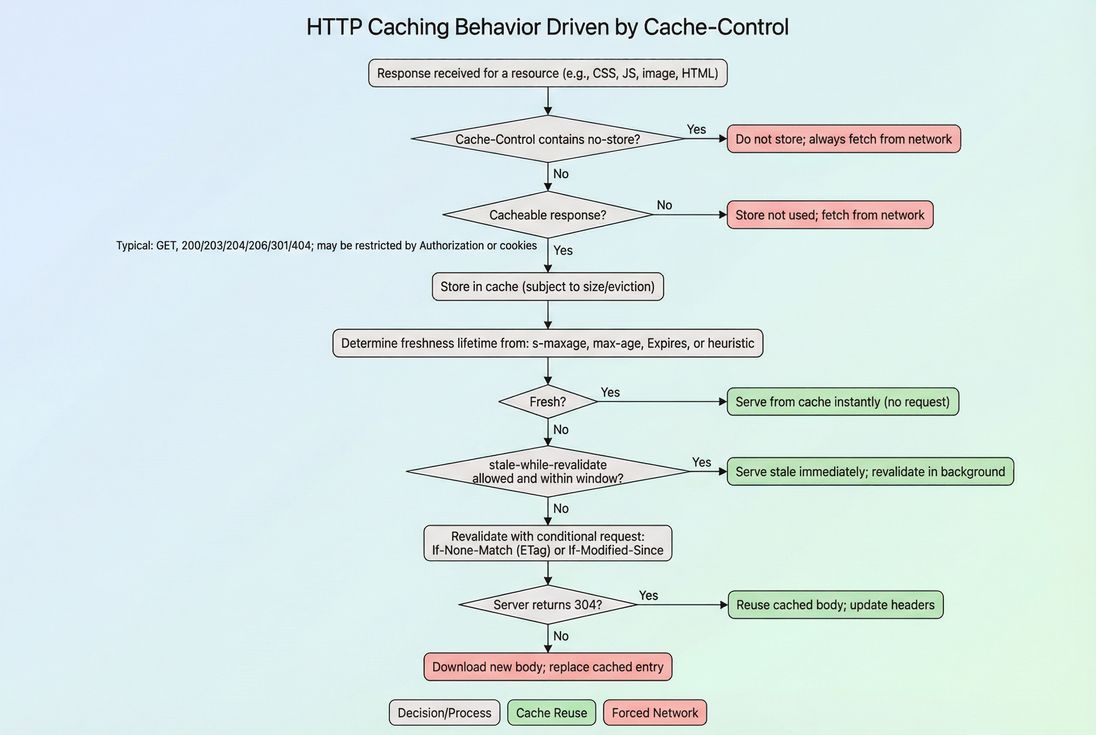

When a browser requests app.css, it gets a response plus headers. From that point on, reuse decisions follow a predictable sequence:

- Is it allowed to be stored at all? (

no-storeblocks storage.) - If stored, is it still "fresh"? (Freshness comes from

max-age/s-maxageorExpires.) - If not fresh, can it be revalidated instead of fully downloaded? (Uses

ETag/Last-Modifiedand can result in a lightweight304 Not Modified.) - If revalidation fails or content changed, download again (a new

200with a new body).

Cache-Control decides whether a resource is reused immediately, revalidated cheaply, or fetched again in full.

What "effective cache TTL" means in practice

Website owners often encounter a "TTL" concept in audits and tools. In plain terms:

- If a file is fresh for 1 year, the browser can reuse it for up to a year without contacting your servers.

- If a file is fresh for 0 seconds, the browser may store it, but it must re-check before reuse (common for HTML).

This is closely related to cache TTL: the real reuse window a user gets, based on your headers and the cache's behavior.

Why revalidation still costs time

A 304 Not Modified is cheaper than a full download, but it still requires:

- DNS/TCP/TLS work (unless the connection is reused)

- A round trip to the server/CDN

- Potential origin load if the CDN can't validate at the edge

That's why long-lived freshness for static versioned files is so valuable.

Which directives actually matter

You'll see many Cache-Control directives in the wild. These are the ones that change real-world performance and risk.

max-age (freshness for browsers and shared caches)

- Meaning: how long the response is fresh.

- Business impact: larger

max-agegenerally improves repeat-visit speed. - Risk: if you reuse the same URL for updated content, users may not get updates quickly.

s-maxage (freshness for shared caches)

- Meaning: overrides

max-agefor shared caches like CDNs. - Use case: cache anonymous HTML at the edge for a short window (e.g., minutes), while keeping browsers more conservative.

public and private

public: response may be stored by shared caches.private: only the browser should store it; shared caches should not.

For personalized pages (account, cart, order history), private reduces the chance of an intermediary cache serving the wrong content.

no-store vs no-cache (commonly confused)

no-store: do not store the response at all (best for sensitive pages).no-cache: may store, but must revalidate before reuse.

For many dynamic HTML pages, no-cache is often a better "stay fresh" strategy than no-store because it still allows conditional requests and can reduce bandwidth.

must-revalidate

- Meaning: once stale, it must be revalidated before reuse.

- Practical note: often paired with

max-age=0on HTML to prevent using stale content.

immutable (great for fingerprinted assets)

- Meaning: the browser shouldn't revalidate while fresh.

- Use case:

app.3f2c1a.css,vendor.a91b7e.js(URLs that change when content changes).

stale-while-revalidate and stale-if-error

stale-while-revalidate: can serve slightly stale content while revalidating in the background.stale-if-error: can serve stale content if the network/server fails.

These can reduce tail latency and improve resilience, especially when paired with CDN vs origin latency.

How long should assets cache?

This is where most sites either leave performance on the table – or create "stale content" incidents. The safe answer is: cache long only when the URL changes when the file changes.

Practical policy table (safe defaults)

| Resource type | Typical change frequency | Safer Cache-Control starting point | Why |

|---|---|---|---|

Versioned CSS/JS bundles (app.[hash].js) | per deploy | public, max-age=31536000, immutable | Fast repeat visits; no revalidation; URL busts cache |

Non-versioned CSS/JS (app.js) | per deploy | public, max-age=300 (or version it) | Reduces staleness risk if URL doesn't change |

| Product images (URL changes per asset) | low | public, max-age=2592000 (30 days) | Good ROI; images are heavy |

| Fonts | low | public, max-age=31536000, immutable (if versioned) | Fonts are render-sensitive (see font loading) |

| HTML documents | high | no-cache (store but revalidate) or max-age=0, must-revalidate | Keeps content fresh while still allowing conditional requests |

| API responses (public, non-user-specific) | medium | depends (often seconds/minutes), plus s-maxage at CDN | Prevents stale business data |

| Cart/checkout/account | very high/sensitive | no-store or private, no-cache | Avoids stale or leaked personalized data |

The Website Owner's perspective

Long caching isn't a "set it and forget it" win. It's a contract: if you tell browsers "this file won't change for a year," you must change the URL when it changes. That's an operational decision (build pipeline, CDN rules, release discipline), not just a header tweak.

The "two-bucket" approach that works

Most high-performing sites separate assets into two buckets:

Immutable bucket (cache for a year)

Files have content-hashed filenames. Any change produces a new URL. Example:/assets/app.3f2c1a.js.Mutable bucket (cache briefly, revalidate often)

HTML and non-versioned endpoints use short caching or mandatory revalidation.

This separation is the simplest way to get aggressive caching without stale incidents.

Interaction with compression and byte savings

Caching and compression stack:

- Compression reduces bytes per request (see Brotli compression and Gzip compression).

- Cache-Control reduces the number of requests and transferred bytes on repeat views.

If your repeat views are slow, you typically need both.

When Cache-Control backfires

Caching issues tend to show up as "weird" bugs rather than obvious speed regressions. Here are the failure modes that matter most.

Stale CSS/JS after a deploy

Symptom: Users report broken layout or old JS behavior after a release.

Cause: Long max-age on non-versioned URLs.

Fix: Add file versioning (hash in filename) and use long-lived caching only on those files. If versioning isn't feasible yet, keep max-age short.

"Why is my CDN not caching?"

Common causes:

- Responses include

privateorno-store - CDN is configured to bypass cache on certain cookies/headers

- Missing

public(some setups require explicit permission) Set-Cookieon responses that you expect to be cacheable

This is where your CDN rules and origin headers must agree. See edge caching for the conceptual model.

HTML cached too aggressively

Symptom: Promotions, prices, or inventory updates don't show quickly.

Fix options:

- Keep HTML as

no-cache(store but always revalidate) - Use CDN caching for HTML only for anonymous users, with short

s-maxage - Purge CDN on critical updates if you rely on longer

s-maxage

Caching breaks personalization

Symptom: Users see the wrong account/cart state.

Fix: Ensure personalized responses are private (browser-only) or no-store (sensitive). Also verify Vary and CDN cache keys if you cache any HTML at the edge.

How to audit and monitor Cache-Control

Step 1: Confirm what's actually being served

Don't guess – inspect response headers on the slow pages:

- Are your biggest files (images, JS bundles, fonts) getting long

max-age? - Are HTML documents being cached in a way that could cause staleness?

- Are you accidentally sending

no-storeon static assets?

A reliable way is to use a waterfall and click into requests to see response headers. In PageVitals, you can do this via the network request waterfall report: /docs/features/network-request-waterfall/.

Also cross-check in PageSpeed Insights because its caching audit is often your first clue that static assets are under-cached.

Step 2: Measure the right before/after

Caching often looks underwhelming in one-off lab runs because they usually represent a cold cache. To see the real benefit:

- Compare first view vs repeat view behavior (requests and transferred bytes).

- Look at field trends (real users), not just lab scores (see field vs lab data).

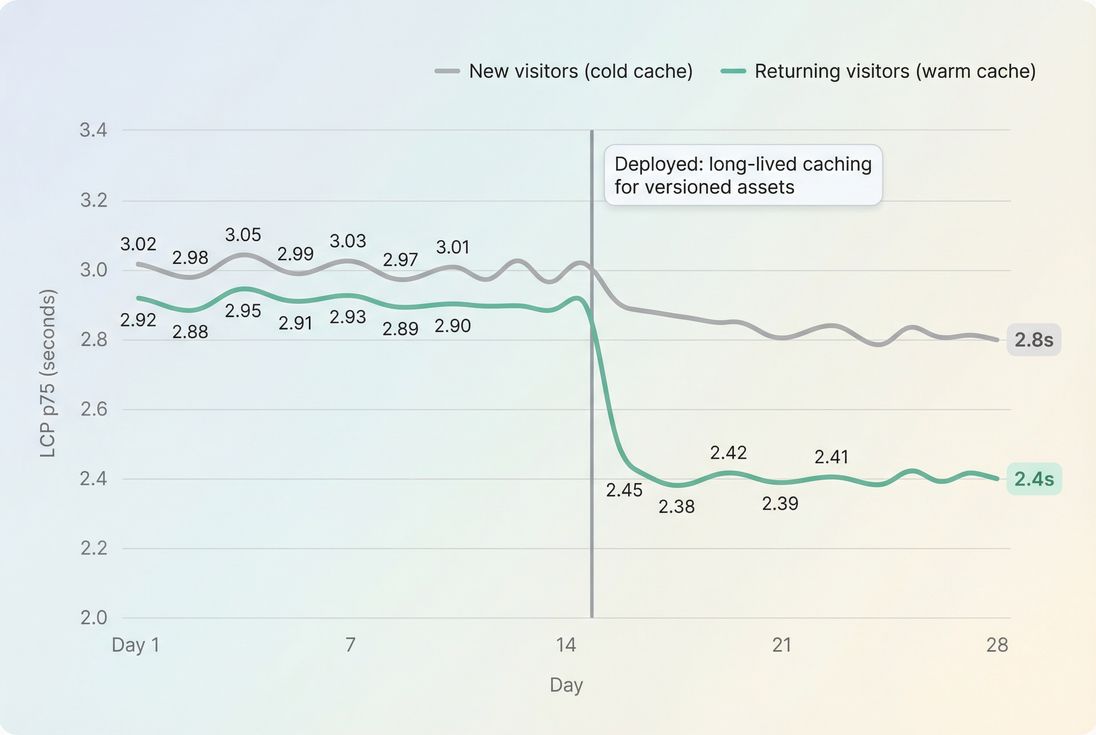

If you're tracking user experience via real user monitoring or CrUX-style datasets (see CrUX data), caching improvements typically show up as:

- Better LCP and overall load time for returning users

- Less variability (fewer slow outliers)

Caching changes often show a bigger speed lift for returning users than for first-time visitors.

Step 3: Watch for regressions

Caching breaks quietly when:

- build pipelines stop hashing filenames

- a CDN rule changes

- an app starts serving static assets with cookies

- a framework update changes default headers

If you use performance budgets, set guardrails around repeat-view transferred bytes or key static resources so "cache policy drift" is caught early. (In PageVitals, budgets are documented here: /docs/features/budgets/.)

The Website Owner's perspective

Treat Cache-Control like an uptime policy: you're balancing speed against correctness. The right operational move is to make "fast and correct" the default (hashed assets + long cache) so you don't have to re-litigate caching on every release.

A practical checklist you can apply today

- Inventory your heaviest assets (JS bundles, hero images, fonts).

- Confirm which assets are versioned (hashed filenames/URLs).

- Set long-lived Cache-Control only on versioned assets (

max-age~ 1 year +immutable). - Keep HTML revalidated (

no-cacheis a common, safe baseline). - Use

s-maxageintentionally if you want CDN caching behavior to differ from browsers. - Re-test and monitor using both lab and field signals (see measuring Web Vitals).

If you do nothing else: make sure your versioned static assets are cached for a long time. That one change typically reduces repeat-view network traffic by multiples – and gives you a noticeably faster site for the customers most likely to buy.

Frequently asked questions

For static, versioned assets (product images, CSS, JS bundles), use long-lived caching like max-age=31536000 and immutable, and change the URL when the file changes. This improves repeat-visit speed dramatically. Keep HTML shorter-lived so pricing, inventory, and promos update quickly.

That audit usually means your static files have a short max-age or no caching headers, so repeat visitors re-download assets. It can also trigger when you rely on validation (ETag/Last-Modified) instead of freshness. Fix by setting a long max-age for hashed assets and separating them from frequently changing files.

You can cache HTML safely, but you need a strategy. Many sites use short max-age plus revalidation (no-cache) so the browser can store HTML but must check before reuse. For CDN caching of HTML, use careful rules, vary by cookies, and purge on updates.

max-age controls how long browsers and shared caches consider a response fresh. s-maxage is for shared caches like CDNs and overrides max-age there. This lets you keep browsers conservative while allowing edge caching for anonymous traffic, reducing origin load and improving TTFB.

Lab tests often run with a cold cache, so caching improvements may look small there. Validate with field data, segmented by new vs returning users. Watch LCP and overall page load time trends after release, and confirm reduced transferred bytes and fewer network requests on repeat views.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial