Table of contents

Network latency explained

Network latency is the quiet "tax" on every page view: it adds delay to each round trip between a shopper's phone and the servers that power your page. On modern ecommerce pages with dozens (or hundreds) of requests across multiple domains, small latency increases turn into visible slowdowns – later product images, slower add-to-cart flows, and more abandoned checkouts.

Network latency is the time it takes for data to travel between a user's device and a server and back again. In web performance discussions, it's most often reflected as round-trip time (RTT) – how long it takes a packet to go from the browser to the server and return. Latency is not bandwidth: you can have fast download speeds and still have a sluggish site if RTT is high.

What network latency reveals

Latency answers a practical question: how "far away" your site feels to real users. That "distance" can be geographic (your origin is in one region), network-driven (mobile carrier routing), or architectural (you rely on many third-party domains).

Here's what latency is – and isn't – in day-to-day website decisions:

- Latency is delay per interaction with a server. If a request requires multiple back-and-forth steps (connection setup, security, redirects), latency compounds.

- Latency is not throughput. Big images are mainly a bandwidth problem, but latency still affects when the image download can start. (See Image optimization and Image compression.)

- Latency is not backend time. Backend time is work your server does after it receives the request. Latency is the travel time to get there and back.

A good mental model: latency affects the start of work. Bandwidth affects how fast the work finishes once it starts.

The Website Owner's perspective: Latency is the difference between a shopper seeing your above-the-fold product photo "immediately" versus waiting an extra beat before anything looks trustworthy. You usually cannot control the user's network – but you can control how many times your page makes them pay that round-trip tax.

What drives latency on real pages

Latency is influenced by several layers, and the important part is that many of them repeat per hostname.

Physical distance and routing

Even at the speed of light, traffic takes time to move across long distances, and real-world routing is rarely a straight line. Common patterns you'll see:

- A US shopper hitting a US edge location: typically low RTT.

- A US shopper hitting an origin hosted in Europe: typically much higher RTT.

- Mobile networks with carrier NAT and changing radio conditions: inconsistent RTT, even within the same city.

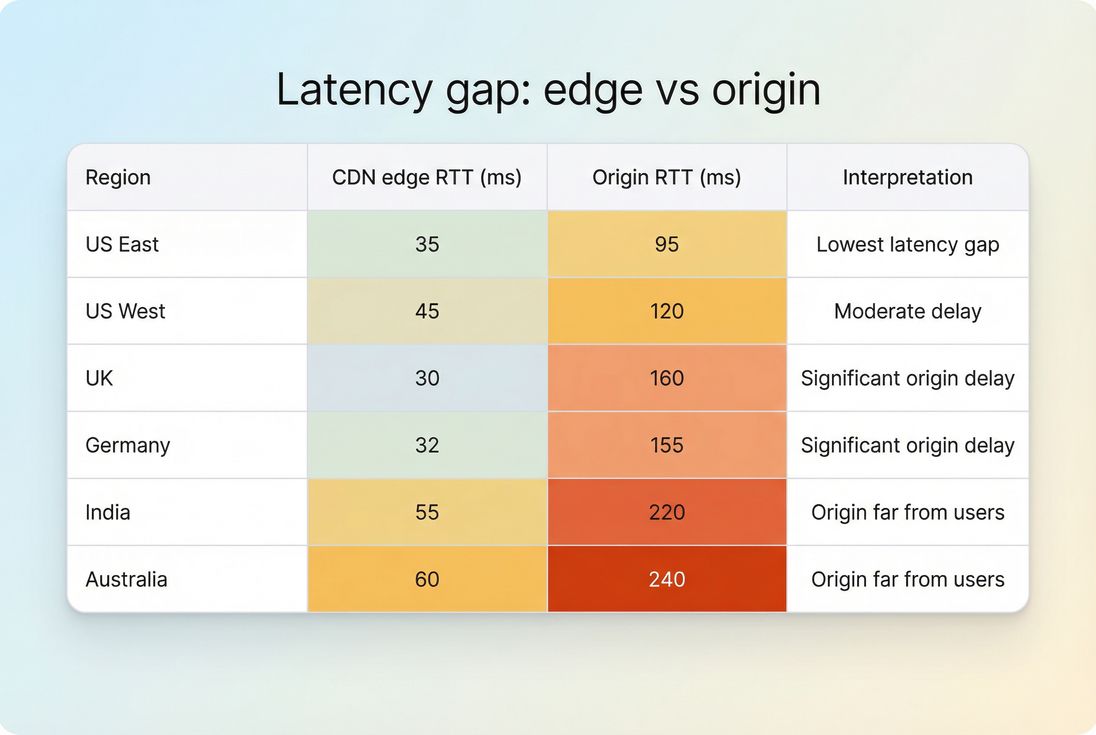

This is why CDNs matter – not because they "speed up the internet," but because they put content closer to users. For deeper context, see CDN performance and CDN vs origin latency.

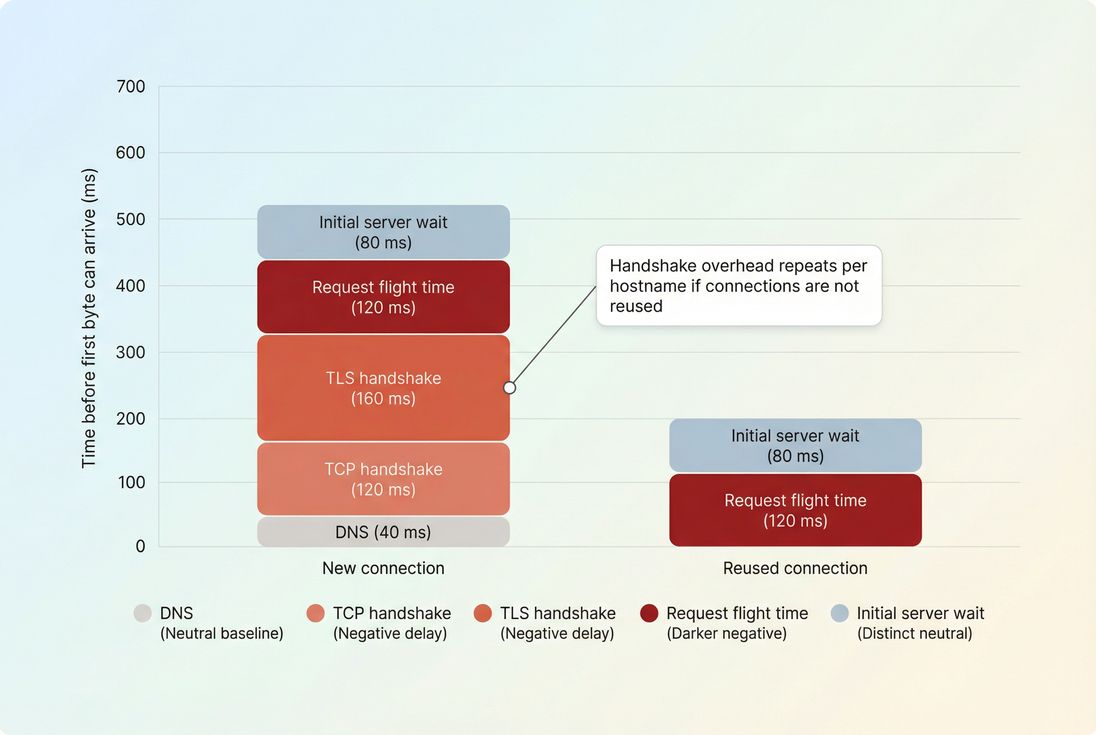

Connection setup costs (DNS, TCP, TLS)

Before a browser can request most resources, it often needs to:

- Resolve DNS (DNS lookup time)

- Establish a TCP connection (TCP handshake)

- Negotiate encryption (TLS handshake)

Each of these steps can require additional round trips – meaning they get slower as RTT increases.

You can reduce repeated setup costs with:

- Connection reuse and fewer hostnames (Connection reuse)

- Preconnect for truly critical third-party origins (Preconnect)

- DNS prefetch as a lighter hint (DNS prefetch)

Too many third-party domains

Every new domain can trigger its own DNS + connect + TLS overhead. Common culprits:

- Tag managers loading multiple vendors

- A/B testing tools

- Chat widgets

- Affiliate and attribution scripts

Even if each script is "small," they can impose large latency costs before they do anything useful. See Third-party scripts.

Protocol and transport choices

Modern protocols help you waste less time:

- HTTP/2 reduces connection overhead by multiplexing many requests over one connection (HTTP/2 performance).

- HTTP/3 can reduce some handshake and loss recovery pain on mobile networks (HTTP/3 performance).

These don't eliminate RTT, but they reduce how often RTT is paid.

How it's measured in practice

"Latency" gets used casually, so you want to be clear what you're looking at. In web performance work, you'll see these common measurements:

RTT and ping-style latency

A basic network measurement is "ping" latency. It approximates RTT but doesn't perfectly match browser traffic. It's useful for sanity checks and regional comparisons. See Ping latency.

In many performance tools and datasets, you'll see RTT explicitly. In PageVitals documentation, RTT is covered as a metric here: Round Trip Time.

Browser timing breakdowns

In browser-side request timing (Navigation/Resource Timing), you typically see phases that imply latency costs:

- DNS time

- Connect time

- SSL time

- Waiting (often used as the request/TTFB wait bucket)

- Content download

When latency rises, you often see it show up as:

- longer connect/SSL (more round trips stretched out)

- longer waiting (because the request and first byte take longer to travel)

- worse performance specifically for cross-origin resources

Waterfalls: the fastest way to diagnose

A request waterfall is where latency becomes obvious because you can see:

- which hostnames are causing repeated setup

- which requests block rendering

- whether connections are reused

- whether redirects are adding extra round trips

If you use PageVitals, this is exactly what the waterfall view is for: Network request waterfall.

The Website Owner's perspective: When someone says "our site feels slow," a waterfall answers: is the delay coming from our origin, our CDN, a payment/analytics vendor, or simply too many domains? That directly changes who needs to fix it (your dev team vs a vendor vs infrastructure).

When latency actually hurts the business

Latency matters most when it delays critical path resources – things the browser needs to show meaningful content and let users complete tasks.

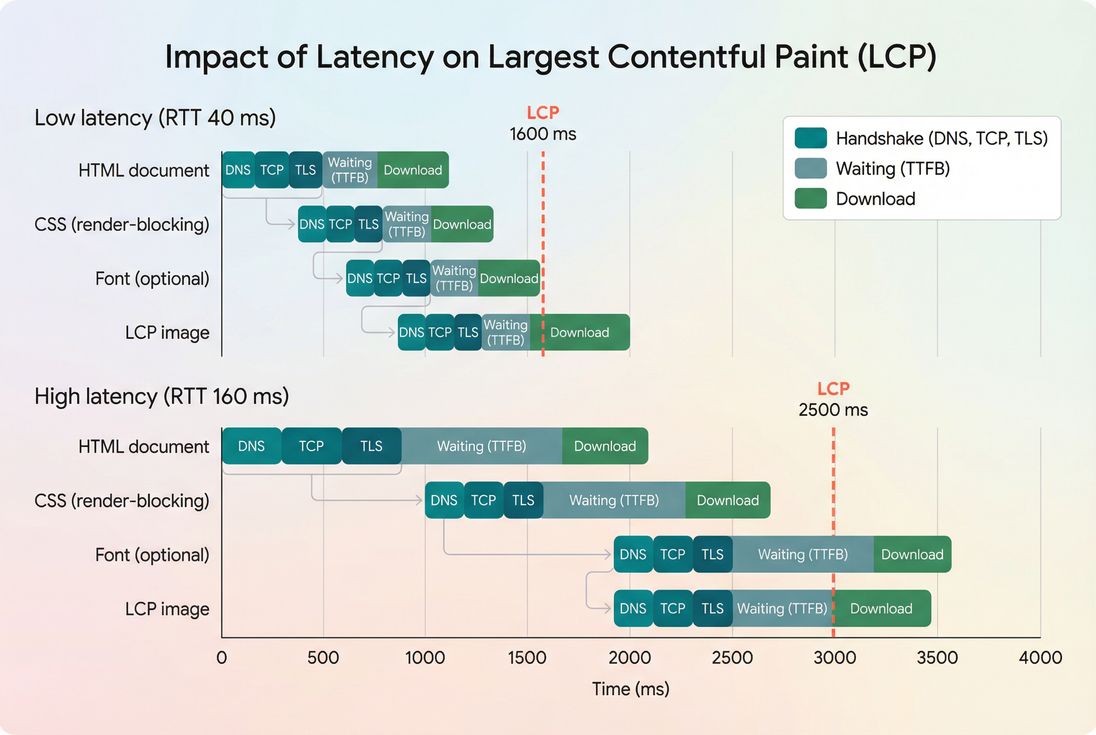

LCP: the most common casualty

Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) is often delayed by latency because the browser needs to fetch:

- HTML (initial navigation)

- render-blocking CSS (Render-blocking resources)

- the LCP image (often a hero/product image)

- sometimes fonts (Font loading)

If those requests require new connections or come from distant origins, LCP slides later.

TTFB: where latency hides in plain sight

Time to First Byte (TTFB) includes both:

- network travel time (latency)

- server processing time (Server response time)

So when TTFB worsens, it's a coin flip until you segment:

- If it's worse mainly in distant geos: likely latency/distance/routing.

- If it's worse everywhere at once: likely backend, database, origin overload, or a blocking layer (WAF, bot checks).

- If it's worse only on cold starts: could be cache misses, serverless cold starts, or origin scaling issues.

INP and "feels slow" interactions

Interaction to Next Paint (INP) is mostly a main-thread responsiveness metric, but latency still appears when interactions require network round trips:

- "Apply coupon" calls an API and blocks UI updates.

- "Calculate shipping" waits on a distant endpoint.

- "Add to cart" depends on a third-party personalization service.

In these cases, optimize the interaction design so the UI stays responsive while the network is in flight (optimistic UI, skeleton states, disable-and-confirm patterns), and reduce the number of blocking calls.

Benchmarks you can actually use

Latency targets vary by geography, device type, and architecture. Instead of chasing a universal "good" number, use ranges to guide decisions and prioritize the biggest wins.

| What you're measuring | Healthy range (common) | Concerning when | Usually means | What to do first |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTT to nearby CDN edge | ~20–80 ms | 120 ms+ in primary market | CDN POP/routing not close, or user base far | Verify CDN serves locally, check geos, validate DNS/CDN config |

| RTT to origin | ~60–150 ms | 200 ms+ for many users | Origin far away, routing issues | Move compute closer, add edge caching, reduce origin hits |

| DNS time | ~0–50 ms | 100 ms+ often | Slow resolvers, no caching, too many hostnames | Reduce hostnames, consider DNS provider, use DNS prefetch |

| TLS/connect time | varies | spikes vs baseline | New connections, no reuse, third parties | Improve Connection reuse, use Preconnect selectively |

Two practical rules:

- Latency costs scale with request count. Reducing requests (HTTP requests) often improves performance even if RTT is unchanged.

- Latency spikes are more damaging on mobile. See Mobile page speed.

How to reduce latency pragmatically

You can't "optimize" the public internet, but you can design your site so it's less sensitive to RTT.

1) Reduce round trips you don't need

Start with the biggest structural wins:

- Remove or delay non-essential third-party scripts (Third-party scripts)

- Cut redirects (each redirect can add another round trip)

- Reduce the number of distinct hostnames on critical pages

If you want a performance budgeting approach (useful for teams), see Performance budgets.

2) Make connections cheaper

- Ensure keep-alive is enabled and connections are reused.

- Prefer HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 where supported.

- Use Preconnect only for truly critical third-party origins (fonts, payment, critical CDNs). Overusing it can waste resources.

- Use DNS prefetch when you're not sure the connection will be needed.

3) Push content to the edge

If your HTML and critical assets require origin trips, distant users will pay that RTT repeatedly.

- Use Edge caching for cacheable content.

- Tune Cache-Control headers and Cache TTL.

- Use Browser caching so repeat visits avoid network work.

This is where latency reduction turns into business impact: repeat shoppers and returning sessions get dramatically faster.

4) Reduce bytes only after the start is fast

Once you've reduced handshakes and origin dependence, then shrinking payloads pays off more consistently:

- Brotli compression or Gzip compression

- Asset minification

- Code splitting and Unused JavaScript

- WebP vs AVIF and Responsive images

Latency and bandwidth interact, but if your requests start late (latency problem), smaller files alone won't fix the "nothing is happening yet" feeling.

5) Treat above-the-fold as a latency budget

Your above-the-fold experience should depend on as few round trips as possible:

- Inline or prioritize critical CSS (Critical CSS)

- Defer non-critical scripts (Async vs defer)

- Avoid render-blocking resources (Render-blocking resources)

- Prioritize LCP resource delivery (especially hero/product images)

See Above-the-fold optimization and Critical rendering path.

The Website Owner's perspective: The goal isn't "the lowest latency number." The goal is fewer moments where a user is waiting on the network before they can see product value or complete checkout. That's a design and architecture decision as much as a hosting decision.

How to interpret changes over time

Latency is noisy, so interpret it like an operator:

Segment before you act

When latency "gets worse," first answer:

- Where? (country/region)

- Who? (mobile vs desktop)

- Which hostnames? (your domain vs third parties)

- Which pages? (home, PDP, collection, checkout)

This is why you should pair lab tests with field data. See Field vs lab data and CrUX data.

Watch for these patterns

- Regional spikes: often CDN POP issues, ISP routing changes, or origin distance.

- Checkout-only spikes: payments/fraud scripts, personalization calls, or different caching rules.

- Only first page view slower: cache warmup, connection reuse issues, or heavy third-party bootstraps.

- Random intermittent spikes: packet loss/congestion; HTTP/3 can sometimes help, but also check third-party reliability.

A practical workflow for owners

If you need a simple, repeatable way to use latency in decisions:

- Start with business pages. Product detail pages, collections, and checkout steps.

- Identify critical hostnames. Your HTML, your asset CDN, fonts, analytics, payments.

- Use a waterfall to find repeated handshakes. Look for DNS/connect/TLS showing up over and over for different domains.

- Reduce cross-origin dependencies above the fold. Make LCP depend on your fastest path.

- Validate with field data segmentation. Confirm improvements in your primary markets and on mobile.

If you're using PageVitals for diagnosis, the most direct views are the Network request waterfall and RTT tracking via Round Trip Time. For broader interpretation of user populations, refer to CrUX data.

Key takeaways

- Network latency is the round-trip delay between users and servers; it compounds across many requests and many hostnames.

- It most visibly hurts LCP and any interaction that waits on the network.

- The biggest wins usually come from fewer round trips: fewer domains, fewer redirects, more connection reuse, and more edge caching.

- Treat latency changes as a segmentation problem before a tooling or hosting problem.

Frequently asked questions

For most US or EU shoppers hitting a nearby CDN, a typical round trip is often under 50 to 80 ms. To your origin, under about 100 to 150 ms is a common target. Higher can still work, but it increases the cost of every request, especially on mobile.

No. TTFB includes network delay plus server delay. A fast network with a slow backend can still produce high TTFB. Conversely, a fast backend far from the user can also produce high TTFB. Separate them by checking geographic patterns, CDN versus origin behavior, and request timing breakdowns.

Latency slows the start of every critical request: HTML, CSS, fonts, images, and API calls. That pushes LCP later because the browser cannot render what it has not received. INP is less directly tied to latency, but network delay can prolong UI updates that wait on API responses.

Sometimes, but switching is usually the last lever. First validate that your CDN is actually serving from nearby locations, that caching is effective, and that third party domains are not dominating the critical path. If CDN latency is consistently high in key regions, a different provider or configuration can help.

Latency can change due to ISP routing shifts, regional congestion, mobile network conditions, CDN point of presence issues, WAF or bot mitigation changes, or DNS changes. That is why you should watch trends by region and device type, and correlate spikes to specific hostnames in your request data.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial