Table of contents

Cumulative layout shift (CLS)

Unexpected page movement is a conversion killer: it causes misclicks (add-to-cart becomes "wishlist"), interrupts reading, and makes your site feel unreliable – even when it's technically "fast."

Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS) is the Core Web Vitals metric that measures how much visible content unexpectedly moves around during page load and early use. Lower is better. A good CLS score means your page feels stable: what the user sees stays where they expect it to be.

What CLS reveals about your site

CLS answers a simple question: Does the page stay put while it loads and becomes usable?

For website owners, CLS is less about "performance scoring" and more about preventing high-intent user errors:

- A shopper tries to tap "Size M" but the options shift and they tap "Size S."

- A user starts reading shipping info, then a banner loads and pushes the text down.

- A checkout field moves mid-typing because address validation UI appears above it.

CLS is one of the three Core Web Vitals and pairs with:

You can have great LCP and INP but still lose trust if the UI "jumps."

The Website Owner's perspective: CLS is a reliability metric. If it's high on product or checkout pages, you're not just "failing a Web Vital" – you're increasing misclick risk, form errors, and abandonment. That shows up as lower conversion rate, lower AOV, and more support tickets.

How CLS is calculated (enough to act)

You don't need the full spec to improve CLS, but you do need to understand what creates a "layout shift" and how multiple shifts add up.

A layout shift is unexpected movement

CLS counts unexpected shifts of visible elements. Expected changes (like a user opening an accordion) generally shouldn't count the same way as surprises during load.

Modern CLS measurement also ignores shifts that happen soon after a user input (for example, right after a tap), specifically to avoid penalizing UI that changes as a direct result of user action.

Each shift has a size score

When a shift occurs, the browser assigns it a layout shift score based on two practical ideas:

- How much of the viewport was affected (more content moved = worse)

- How far the content moved (bigger jump = worse)

In the official model, that per-shift score is:

- layout shift score = impact fraction × distance fraction

Think of it as: how much stuff moved multiplied by how far it moved.

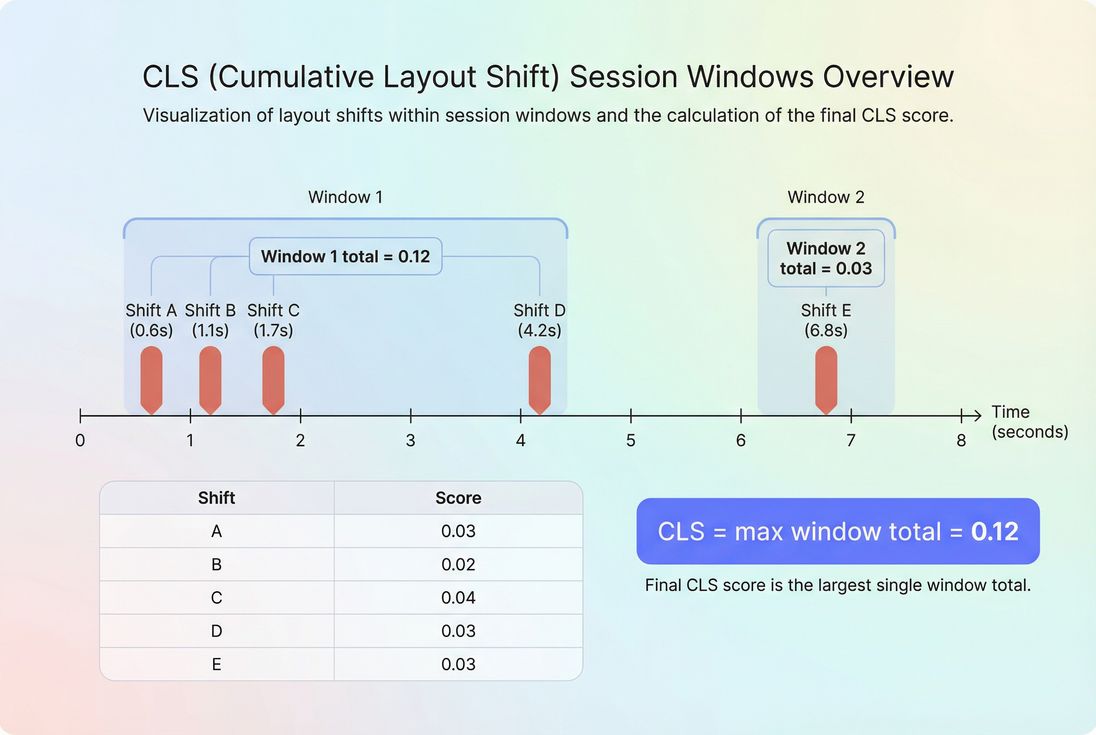

CLS is not the sum of the entire page lifetime

CLS is calculated over a session window (to avoid a page being penalized forever). In plain terms:

- Shifts are grouped when they happen close together.

- A window closes when there's a long enough pause between shifts, and windows have a maximum duration.

- The CLS value reported is the worst (largest) window's total score, not a never-ending accumulation.

This matters for real sites because many shifts come in bursts: hero image loads, then fonts swap, then a promo bar injects.

When CLS breaks on real websites

Most CLS problems come from a handful of repeatable patterns. The fastest way to lower CLS is to map your site's shifts to these causes.

Images and media without reserved space

If an image, video, or iframe appears without known dimensions, the browser initially lays out the page without it, then shifts content when it arrives.

Common culprits:

- Product gallery images missing width/height (or CSS aspect ratio)

- Embedded video players

- Social embeds and maps

- User-generated content blocks

Fix approach: reserve space using explicit dimensions, aspect-ratio boxes, or stable placeholders. This is part of disciplined image optimization and responsive images.

Ads, banners, and cookie notices inserted above content

Late UI insertion is the #1 "it jumped under my finger" scenario, especially on mobile.

Examples:

- Promo bars that push the header down

- Cookie banners that insert at the top instead of overlaying

- "Install our app" banners

- Email capture popups that shift the layout

Fix approach: do not push existing content. Overlay (fixed positioning) or reserve a fixed slot from the start. If you run lab tests and cookie UI is contaminating results, see the guide on removing cookie consent banners from your Lighthouse tests.

Web fonts swapping and reflowing text

When a custom font loads late, text can change width/height, causing reflow. You'll usually notice it as:

- Headlines wrap differently after load

- Buttons grow/shrink as font metrics change

Fix approach:

- Optimize font loading (preload critical fonts, choose the right loading strategy)

- Prefer metric-compatible fallback fonts and modern font techniques (where applicable) to reduce reflow

- Ensure above-the-fold text doesn't depend on late font loads (ties into above-the-fold optimization)

Late-loading CSS and JS that changes layout

If critical CSS arrives late, the page can render with incomplete styling, then "snap" into the final design.

Common causes:

- Render-blocking CSS not handled well (see critical CSS and render-blocking resources)

- JS that injects DOM above existing content

- A/B testing tools that rewrite page structure after render

- Personalization widgets that change headers, product grids, or hero modules

Fix approach:

- Make initial layout stable with critical styles

- Avoid DOM insertions above existing content; if you must, reserve space

- Reduce JS churn via code splitting and eliminating unused JavaScript

"Helpful" components that resize after data arrives

Even first-party UI can cause CLS:

- Shipping estimator expands once it gets location data

- Reviews module loads and pushes content down

- "Back in stock" and financing widgets expand after API responses

Fix approach: skeletons and placeholders that match final height, plus careful component design so content expands downward in reserved sections rather than pushing primary actions around.

How to interpret CLS changes

CLS is unusually sensitive to "small" front-end changes. That's good (it catches regressions quickly), but it also means you should interpret spikes correctly.

Use thresholds, not perfection

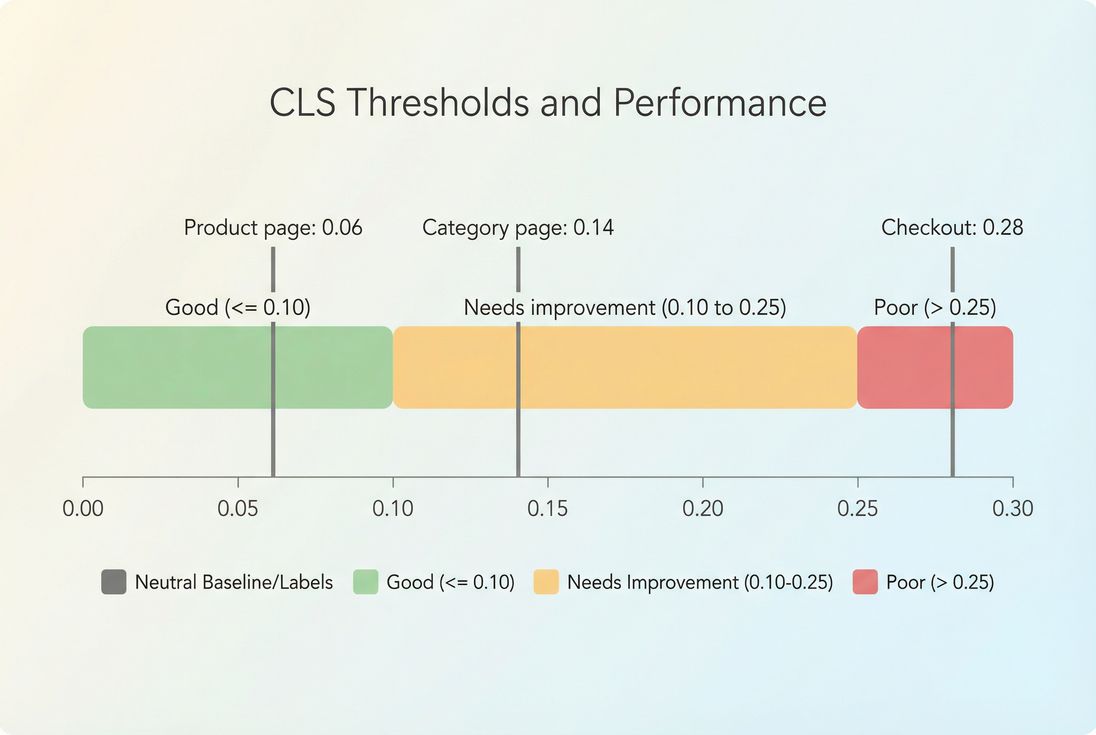

Google's commonly used thresholds:

| CLS range | Meaning | What users feel |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0.10 | Good | Stable, low misclick risk |

| 0.10–0.25 | Needs improvement | Noticeable movement on some loads |

| > 0.25 | Poor | Frequent disruption, high frustration |

If you're at 0.11, don't panic – but treat it like an early warning. If you're at 0.30 on checkout, prioritize it immediately.

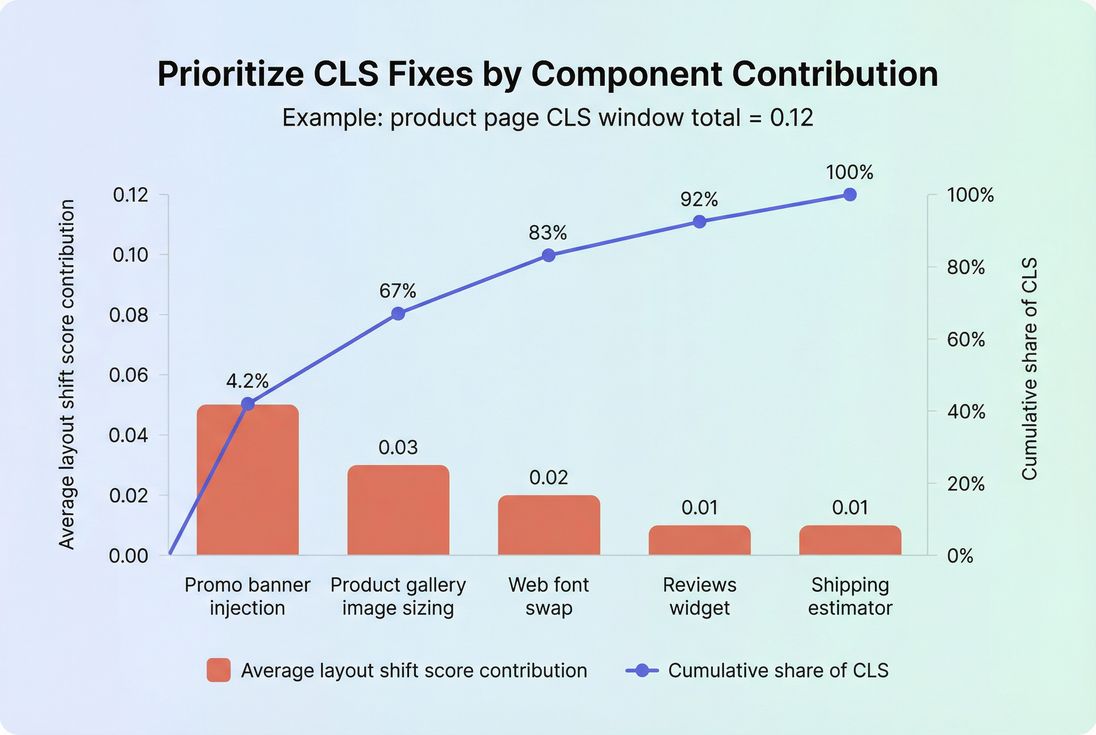

Look for "template-level" problems

CLS is often driven by shared templates:

- Category pages share the same filter and product grid components

- PDPs share the same gallery and buy box

- Checkout shares the same address and payment modules

Fixing one template component can improve hundreds or thousands of URLs.

The Website Owner's perspective: The right question isn't "Why is this one URL bad?" It's "Which shared component is destabilizing an entire revenue-critical template?" That's how you get leverage: one fix, site-wide stability gains.

Expect differences between lab and field

CLS can look "fine" in a lab run and still be bad for real users, or vice versa.

Why:

- Third-party scripts may behave differently for different geos, devices, or consent states

- Real users have slower CPUs and networks (see mobile page speed)

- Cached vs uncached font and asset behavior can change shifts (related to browser caching and Cache-Control headers)

This is why the distinction between field vs lab data is especially important for CLS.

How to measure and debug CLS efficiently

Treat CLS like a triage workflow: confirm it's real, localize the offending element, then prevent recurrence.

Step 1: confirm with field data

Field CLS reflects what users actually experience. Two common sources:

- Your own RUM implementation

- Chrome's anonymized dataset (see CrUX data)

If you're using PageVitals Field Testing, start with:

- The metric definition and behavior: /docs/metrics/cumulative-layout-shift/

- The field report view: /docs/features/field-testing/web-vitals/cls-report/

What to look for:

- Which page groups/templates have the worst CLS

- Whether CLS is worse on mobile than desktop

- Whether the issue is persistent or tied to a recent release/experiment

Step 2: reproduce in lab to identify the element

Lab tools help you find what moved:

- Lighthouse and DevTools often highlight "layout shift regions"

- Synthetic tests let you compare runs and spot patterns

If you're using PageSpeed Insights, use it to get a quick sense of whether CLS is a lab-only artifact or consistent with field.

Practical debugging tips:

- Record a performance trace and watch for shifts during early load

- Disable third-party scripts temporarily to isolate injected UI

- Test with a cold cache and warm cache (font behavior often changes)

Step 3: quantify the business risk

Not every shift is equal. Prioritize by:

- Location: shifts near primary CTAs (add to cart, checkout, sign up) are more damaging than shifts far below the fold

- Timing: shifts that happen while users are likely to interact (early, around LCP) are higher risk

- Frequency: a small shift that happens on every load can be worse than a large shift that happens rarely

Fixes that reliably reduce CLS

You'll get the biggest gains by fixing CLS at the source: reserve space and stop late insertions from pushing content.

Reserve space for media and embeds

Do this first – it's common and high-impact.

Checklist:

- Ensure

<img>has width and height or an equivalent aspect-ratio strategy - Use stable placeholders for iframes and embeds

- Avoid replacing placeholders with different-sized content

This pairs well with general image compression and modern formats like WebP vs AVIF, but the CLS win is primarily from predictable dimensions, not file size.

Make banners and UI overlays non-shifting

Rules of thumb:

- If it appears late and sits above content, it will probably hurt CLS.

- Prefer overlays (fixed/sticky) that don't reflow the document, or reserve a permanent slot.

For cookie notices:

- Reserve space from initial render if it must be in-flow

- Otherwise overlay it and ensure it doesn't cover primary actions

Stabilize fonts

Font-related CLS can be subtle but widespread.

Actions that typically help:

- Preload critical fonts used above the fold

- Use a loading approach that avoids surprise reflow

- Choose fallback fonts with similar metrics to reduce text resizing

See font loading for deeper strategies and tradeoffs.

Prevent layout changes from late CSS

If you see "unstyled then styled" behavior:

- Inline or otherwise prioritize critical CSS for above-the-fold layout (see critical rendering path and critical CSS)

- Defer non-critical CSS safely (without causing late reflow)

- Keep your CSS lean via unused CSS and asset minification

Tame third-party scripts

Third-party scripts are frequent CLS offenders because they inject content you don't fully control:

- Chat widgets expanding from a small button to a tall panel

- Review widgets loading variable-height content

- Tag managers injecting banners

Mitigations:

- Load third parties later or conditionally where possible

- Give them a reserved container with a fixed min-height

- Avoid injecting above key content; place containers lower in the DOM

This fits into a broader strategy for third-party scripts and managing JS execution time.

Keeping CLS from regressing

CLS regressions often come back when teams add new content injections, new fonts, new ad slots, or experiment scripts. Prevention is mostly process.

Add a stability budget

Treat CLS like a release gate, similar to a broken checkout test:

- Set a target per template (PDP, PLP, checkout)

- Fail builds or block releases when CLS exceeds the threshold

If you use PageVitals, performance budgets are documented here: /docs/features/budgets/. For automation paths, see the CI/CD options like the /docs/ci-cd/github-action/ or /docs/ci-cd/cli/.

Standardize layout-safe component patterns

Give your developers a "safe defaults" toolkit:

- A responsive media component that always reserves space

- A banner slot that exists in the DOM from first render (even if empty)

- A ruleset for third-party embeds (fixed containers, no top insertion)

This reduces CLS incidents without slowing down shipping.

Monitor by template, not just site-wide

A site-wide average can hide a broken money page. Your monitoring should let you answer:

- Is checkout stable?

- Are paid landing pages stable?

- Did an experiment cause shifts only on mobile?

If you're setting up measurement for the first time, it helps to review Measuring Web Vitals so you understand why different tools may not match exactly.

If you remember one principle, make it this: CLS is usually fixed by reserving space and eliminating late layout changes. Do that consistently – especially above the fold – and your site will feel calmer, more trustworthy, and easier to buy from.

Frequently asked questions

Aim for CLS of 0.1 or lower on your key templates like homepage, category, product, and checkout. Between 0.1 and 0.25 usually means users are seeing noticeable movement that can cause misclicks. Above 0.25 often correlates with user frustration and lower conversion rates.

Many marketing tools inject UI after initial render: banners, chat widgets, A/B testing variants, recommendation carousels, or form enhancements. If they push existing content down instead of overlaying in reserved space, CLS rises. Ask vendors for fixed-size containers, delayed insertion below the fold, or CSS transforms.

Yes. A page can have great LCP and still feel broken if content moves while users try to read or tap. CLS is about visual stability, not speed. On mobile especially, small shifts can move buttons under a finger, causing wrong taps, cart errors, and support tickets.

Start with lab tools to reproduce the shift and identify the element that moved, then validate impact with field data. Look for patterns: late-loading images without dimensions, injected banners above content, font swaps, and third-party iframes. Fix the biggest template offenders first, not random one-off pages.

Prioritize based on business impact and current scores. If CLS is poor, fix it quickly because the remedies are often straightforward and reduce misclick risk. If CLS is already good, focus on LCP and INP for broader speed and interactivity gains. Monitor all three under Core Web Vitals.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial