Table of contents

Performance budgets explained

A website rarely "gets slow all at once." It gets slow one small decision at a time: a new tag for a campaign, a bigger hero image, another app, a quick CSS tweak that shifts layout, a personalization script that blocks the main thread. Performance budgets exist to stop that slow drift – before it shows up as lost conversions, higher paid media costs, and support tickets about checkout issues.

A performance budget is a set of measurable limits (for example, LCP under 2.5 seconds, total JS under 200 KB, or third-party requests under 10) that a page or page type must stay within. If a change exceeds the limit, it's treated like any other requirement failure: fix it, change the plan, or explicitly accept the tradeoff.

If you want the short mental model: a budget is how you turn "we care about speed" into "we will not ship regressions."

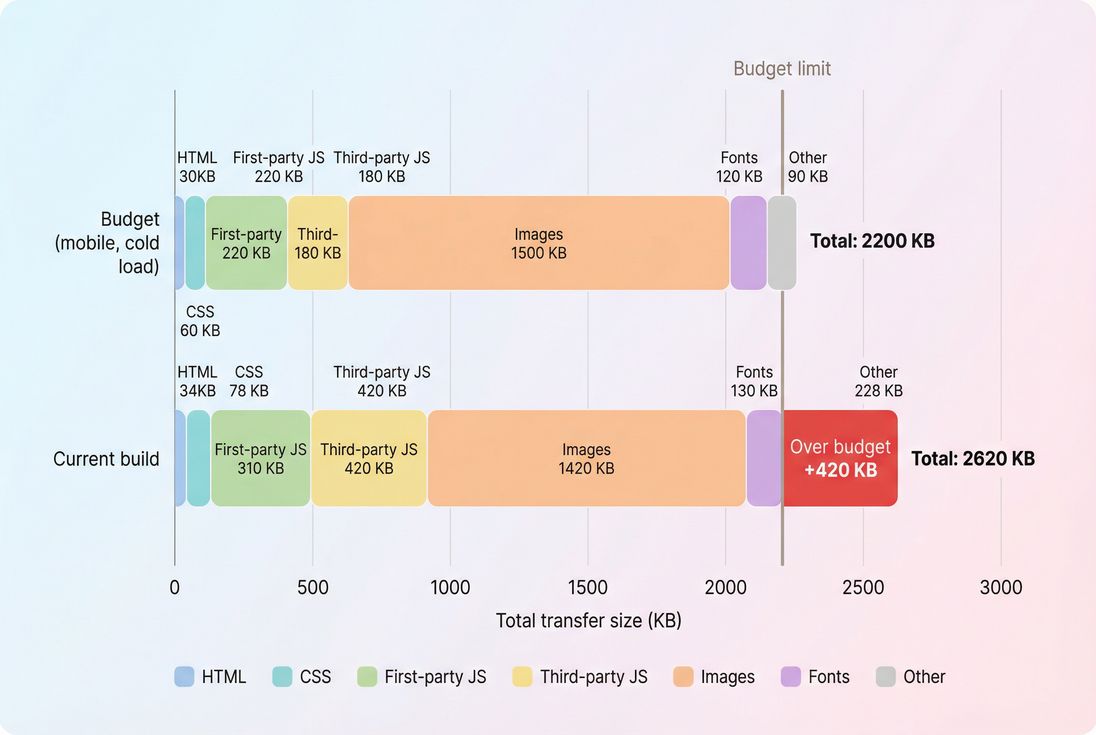

Budgets work best when they're concrete: this view makes it obvious which category (third-party JS) consumed the most headroom and caused the regression.

What budgets actually prevent

Performance budgets prevent three common failure modes:

Silent regressions

You ship a "small" change, but your JavaScript bundle size grows and INP slowly deteriorates until it becomes a business problem.Local optimization with global damage

A team improves one page but adds sitewide scripts that hurt every page's critical rendering path.No way to say no

Without numbers, every new widget sounds harmless. Budgets give you a neutral rule: "We can add it if it fits."

The Website Owner's perspective: A budget turns performance from a debate into a decision. When a vendor says their script is lightweight, you can respond with, "We have a third-party budget. If it pushes us over, we'll need to remove something else or load it later."

Choosing the right budgets

A useful budget is tied to outcomes you care about (conversion rate, retention, SEO visibility) and to the mechanics that typically break on real sites (JS execution, third-party tags, heavy images).

Start with Core Web Vitals budgets

For most sites, the first budgets to set are the ones tied to user experience and measured broadly:

- LCP budget (loading experience): see LCP

- INP budget (responsiveness): see INP

- CLS budget (visual stability): see CLS and layout instability

- Often helpful as a supporting constraint: TTFB budget: see TTFB

If you only set one, set LCP. If you run ecommerce, set LCP and INP (cart/checkout pain is expensive).

Add "cause" budgets that prevent regressions

Vitals tell you that you got slower; cause budgets help prevent why you got slower:

- Total JS transferred and first-party JS transferred

- Third-party JS transferred and/or number of third-party requests (common regression source): see third-party scripts

- Main-thread work / long tasks indicators: see long tasks and reduce main thread work

- Number of HTTP requests: see HTTP requests

- Image weight and LCP-image rules: see image optimization, responsive images, and WebP vs AVIF

These budgets create a "pressure valve": if someone really wants a new feature, you can require they "pay for it" by removing something else or implementing it differently (for example, code splitting).

Budget by page type, not "the site"

Most businesses have a handful of templates that drive revenue:

- Home

- Category/collection (SEO + browsing)

- Product detail (conversion)

- Cart

- Checkout steps (conversion + trust)

Each template needs its own budgets because their content and scripts differ.

The Website Owner's perspective: Your checkout shouldn't lose budget headroom because the marketing team updated the homepage hero. Separate budgets by template so the pages that print money get protected the most.

Practical starting budgets (ecommerce)

These are starting points, not universal laws. Your tech stack, audience devices, and geography matter. But if you need something you can adopt this week, this is directionally solid:

| Budget type (mobile) | Warning | Fail | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCP (key pages) | 2.3 s | 2.5 s | Protects perceived load speed and conversion |

| INP (cart/checkout) | 150 ms | 200 ms | Protects responsiveness under real interaction |

| CLS (sitewide) | 0.05 | 0.10 | Protects trust and prevents mis-clicks |

| TTFB | 600 ms | 800 ms | Early indicator of backend/CDN issues |

| Total JS (per page) | 250 KB | 350 KB | Common driver of LCP/INP regressions |

| Third-party JS | 80 KB | 150 KB | Usually the least controlled, most harmful |

| Image transfer | 1200 KB | 1800 KB | Biggest contributor on media-heavy pages |

| Requests (document + subresources) | 60 | 90 | Too many requests increases contention |

To interpret this table correctly: "Warning" is the point where you investigate; "Fail" is the point where you block a release or require sign-off.

How budgets are calculated in practice

A budget is just a comparison between measured performance and a target threshold. The hard part is picking what you measure, where you measure it, and how strict you are.

Lab budgets vs field budgets

You'll see two major data sources in performance work:

- Lab (synthetic) tests: controlled runs with a defined device/network. Great for catching regressions.

- Field (real user) data: what real visitors experienced across devices/networks. Great for business truth.

If this distinction is fuzzy internally, share field vs lab data with your team.

A common, effective setup:

- Lab budgets: used as a release gate (fast feedback, repeatable)

- Field budgets: used as a trend guardrail (are we harming real customers?)

You can also use CrUX data as a field benchmark, especially for SEO-focused pages.

Pick the percentile that matches the risk

Field performance is not one number. It's a distribution.

For business protection, the most common choice is p75 (the "typical slow experience"), because it aligns with how Core Web Vitals are commonly evaluated in aggregate reporting. Budgets based on medians can hide pain for a meaningful slice of users.

Define the test conditions you care about

A budget without conditions is easy to "pass" by accident.

At minimum, define:

- Device class: mid-tier mobile is usually the revenue reality

- Network: 4G-ish for modern mobile, and optionally a "worse case" 3G-like profile for stress testing

- Cache state: cold load vs warm load (both matter; cold is more punishing)

This connects directly to concepts like mobile page speed and network latency.

Budgets can be pass/fail or headroom-based

Two common styles:

Hard limits (pass/fail)

Example: "Product page LCP must be <= 2.5s."Headroom budgets (protect future growth)

Example: "Product page JS must stay under 250 KB even if it could be higher today."

Headroom matters because your site will grow – more personalization, more analytics, more variants, more internationalization. Without headroom, you'll hit the wall during the next big initiative.

The Website Owner's perspective: Headroom is what lets you say yes to a future campaign without breaking performance. If you operate at the limit all year, every new initiative becomes a fire drill.

What influences performance budgets the most

When teams miss budgets, it's usually not a mystery. It's a familiar set of culprits.

JavaScript: transfer size and execution

JS hurts budgets in two ways:

- Download and parse cost (especially on mobile)

- Execution cost that blocks rendering and interactions

Useful deeper reads:

If you repeatedly miss LCP and INP budgets at once, JS is a prime suspect.

Images: LCP's favorite bottleneck

On most ecommerce pages, the LCP element is an image (hero, product image).

Budget killers include:

- oversized images (wrong dimensions)

- wrong formats (serve WebP or AVIF where supported)

- missing preload for the LCP image: see preload

- too many images loaded eagerly: see lazy loading

Related: above-the-fold content and critical CSS.

Third-party scripts: small additions, big consequences

Third-party scripts often:

- add multiple downstream requests

- run long tasks on the main thread

- inject layout-shifting elements (CLS risk)

- delay interaction readiness (INP risk)

If you want budgets to stick, you typically need a third-party intake rule: every new tag must show its cost and where it loads.

Backend and delivery: TTFB and caching

If your TTFB budget fails, front-end tuning won't save you.

Common levers:

- CDN performance and CDN vs origin latency

- edge caching

- Cache-Control headers and browser caching

- compression: Brotli compression or Gzip compression

TTFB is also shaped by connection setup (DNS/TCP/TLS) on cold visits:

How website owners interpret changes

Budgets are only useful if a budget change triggers the right decision.

If you exceed a budget once

Treat it like a regression:

- What changed? (release diff, tag change, content change)

- What category grew? (JS, third-party, images, requests)

- Which metric moved? (LCP vs INP vs CLS)

- Is it isolated to one template? (product vs category)

This is where a network request waterfall helps: it shows which resource delayed rendering. (See also render-blocking resources.)

If you keep trending toward the limit

That's performance debt.

Common reasons:

- "Just this once" third-party additions

- A/B testing frameworks accreting scripts

- Design system CSS growing without pruning: see unused CSS

- Shipping more code to every route instead of splitting

At this stage, the best decision is often structural: invest in code splitting, reduce global bundles, or change tag governance.

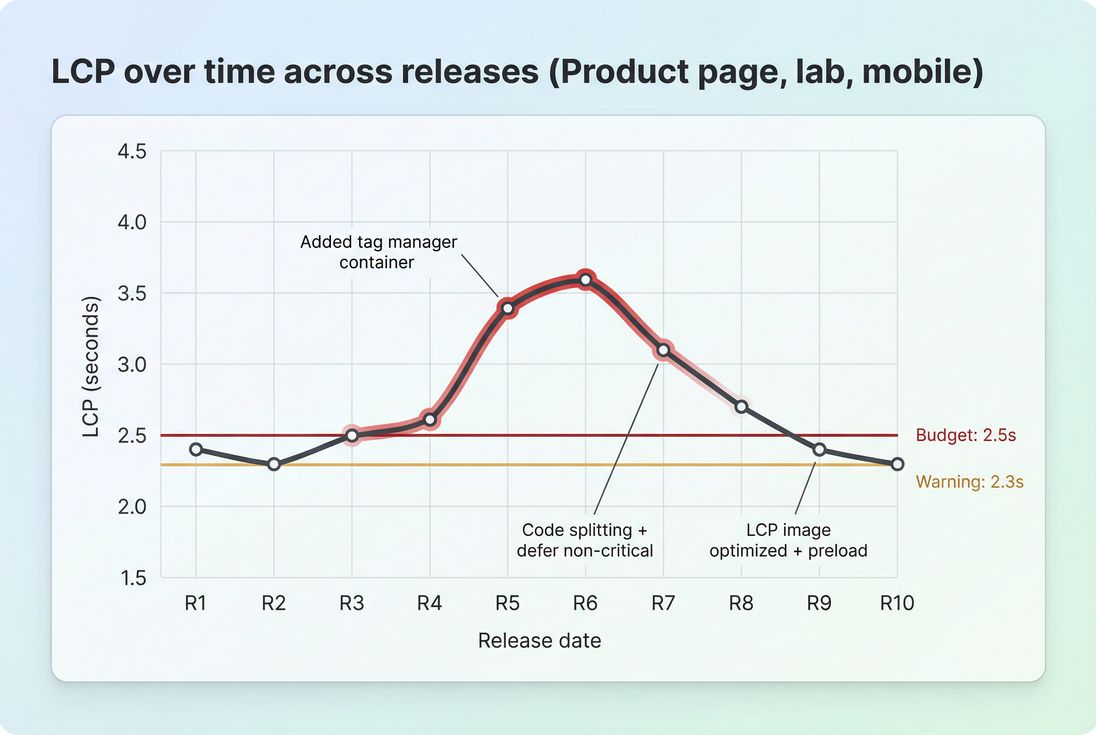

If you suddenly improve a lot

Don't just celebrate – lock it in with tighter budgets.

A big improvement can come from:

- image format conversion and resizing: image compression

- removing render-blocking CSS/JS

- caching improvements and shorter server work: server response time

Once you've paid the cost to improve, budgets stop you from drifting backward.

Enforcing budgets in your workflow

Budgets fail when they live in a spreadsheet. They succeed when they are enforced where changes happen: releases.

Put budgets in CI/CD

The most effective pattern is: every PR or deploy runs a test, and budgets decide pass/fail.

If you use PageVitals, start with the documentation for:

- Performance budgets

- CI/CD setup options like CLI CI/CD or GitHub Actions CI/CD

The goal is simple: prevent "we'll fix it later" from becoming "this is just how fast we are now."

A budget line turns a performance trend into an operational signal: releases R5–R8 clearly violated the LCP target, forcing either rollback, optimization, or explicit tradeoffs.

Assign ownership by template

Budgets need an owner, or regressions become everyone's problem and nobody's priority.

A practical ownership model:

- Product/engineering owns first-party JS, rendering, and template structure

- Marketing owns third-party additions

- Design owns CLS risks and font behavior: see font loading performance

- Platform/ops owns TTFB, CDN, caching

Separate "launch" budgets from "steady-state" budgets

Big changes (replatforming, redesigns) can temporarily strain performance. You can plan for that without giving up control:

- Launch budgets: slightly looser, time-boxed

- Steady-state budgets: tighter, enforced continuously

The key is time-boxing. Otherwise, "temporary" becomes permanent.

The Website Owner's perspective: If your redesign is allowed to miss budgets, you're not just accepting a slower site – you're accepting higher acquisition costs and lower conversion until someone funds a fix. Time-boxed launch budgets keep pressure on to finish performance work.

What to do when a budget is exceeded

Budget failure is not a crisis. It's a prioritization tool.

Step 1: Identify which budget broke

- If LCP broke: check LCP element, render-blocking resources, image delivery, and TTFB.

- If INP broke: look for long tasks and heavy JS, especially third-party.

- If CLS broke: find late-inserting elements (banners, ads, fonts).

You'll often use:

Step 2: Decide the "fix vs tradeoff" path

Common decision paths:

- Optimize (preferred): compress images, split code, defer non-critical scripts, reduce main-thread work.

- Defer: load non-critical features after first render or after interaction.

- Replace: choose a lighter vendor/library.

- Remove: delete low-value scripts and experiments.

- Accept with sign-off: rare, explicit, documented.

This is where budgets pay off: they force explicit tradeoffs instead of accidental ones.

Step 3: Prevent recurrence

If the same type of regression repeats, your process is the real issue.

Examples:

- Third-party regressions → add a third-party approval checklist and a budget cap.

- JS bloat → enforce route-level code splitting and review bundle diffs.

- Image regressions → enforce responsive image rules in templates and CMS guidance.

Budgeting across real-world conditions

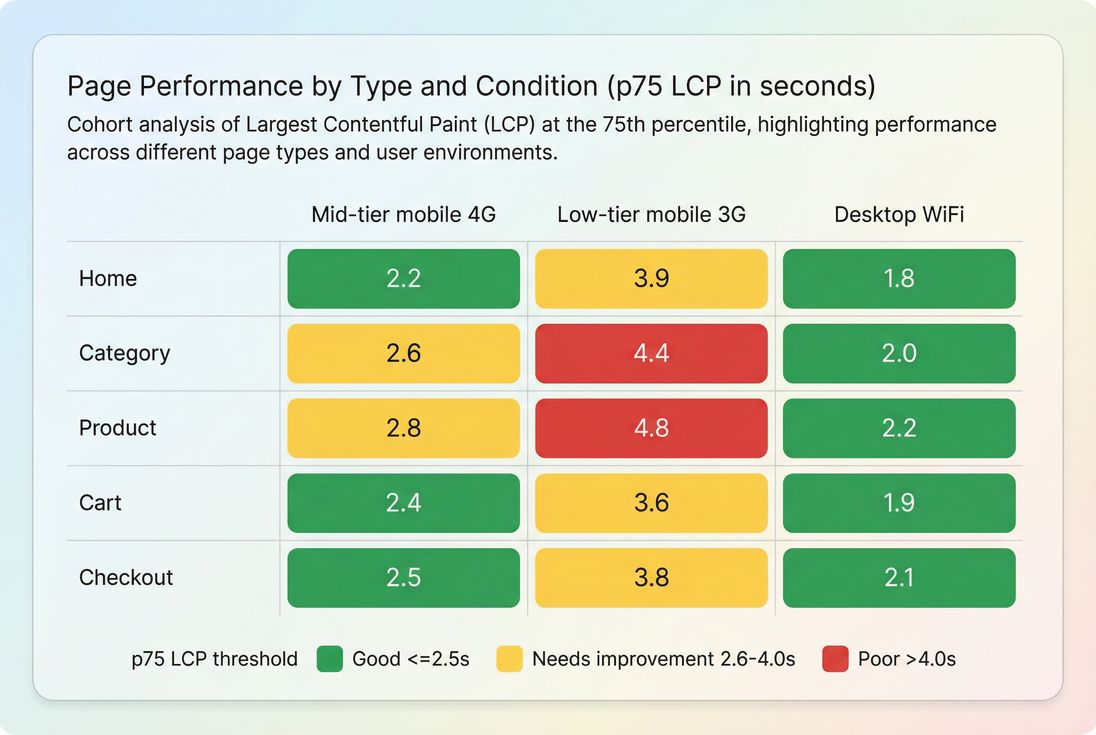

A single budget number can hide where users actually struggle. A clean way to surface this is to review budgets by page type and typical connection/device scenarios.

Template-level budgets become more actionable when you can see which page types fail under realistic conditions – often product and category pages on slower mobile connections.

This kind of breakdown changes decisions fast. For example, it tells you:

- Your "average" LCP might look okay, but product pages on slower phones are failing, which is exactly where conversion happens.

- The right fix may be image delivery and critical rendering path work, not another round of generic minification.

A simple rollout plan (that sticks)

If you want to implement budgets without a multi-month project:

- Pick 3–5 critical templates (home, category, product, cart, checkout)

- Set 2–3 budgets per template

Start with LCP + INP (where relevant) + a JS or third-party budget - Baseline current performance

Use consistent lab conditions; compare with field trends if available - Add a warning and a fail threshold

Warning triggers investigation; fail blocks or requires sign-off - Enforce budgets in release workflow

This is where budgets become real (see /docs/features/budgets/) - Review budgets monthly

Tighten if you improve, or redesign the architecture if you keep slipping

If you need automation, the Budgets API can support programmatic enforcement and reporting.

If you're already tracking Core Web Vitals, performance budgets are the missing operational layer: they translate monitoring into guardrails that keep your site fast as the business changes. For related foundations, see Core Web Vitals and measuring Web Vitals.

Frequently asked questions

A performance budget is a set of hard limits for page speed and page weight, like LCP under 2.5 seconds or total JavaScript under 200 KB. It turns performance into a pass fail requirement, so new features cannot quietly make checkout slower.

Start with Core Web Vitals budgets for key templates: LCP for product and category pages, INP for cart and checkout, and CLS sitewide. Then add weight budgets for JavaScript and third party scripts, because they are the most common source of sudden regressions.

Use both. Lab budgets catch regressions before release because they are repeatable, while field budgets confirm real visitor impact across devices and networks. A common approach is to enforce lab budgets in CI and review field p75 trends weekly for drift.

Treat it like any other constraint. Identify which change consumed the budget, decide whether to optimize, remove, or defer it, and only increase the budget with explicit approval. The goal is to avoid normalizing regressions that compound over months.

Very strict, because third party scripts often add network requests and main thread work that hurt INP and LCP. Set a third party budget and require each new tag to justify its cost. If the tag is essential, consider loading strategies that reduce impact.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial