Table of contents

Removing unused CSS

Unused CSS rarely "breaks" a page. It quietly taxes every new visitor with extra bytes, extra render-blocking time, and extra styling work – especially on mobile. That shows up as slower first impressions, lower conversion rates on landing pages, and higher paid-media bounce when the page feels sluggish.

Removing unused CSS means reducing (or delaying) CSS rules that the current page does not need to render the initial view. In plain terms: you stop shipping styling the user won't see or use, at least not right away.

What unused CSS really means

When tools say "unused CSS," they usually mean:

- CSS bytes downloaded for the page

- that did not match any element during the test window (often initial load, sometimes plus a short idle period)

- for a specific viewport size (mobile vs desktop can be very different)

This is why unused CSS is not a moral judgment about your stylesheet. It's a delivery efficiency signal: did this page need all that CSS right now?

Why it slows pages down

CSS hurts performance in three main ways:

Network transfer

- Especially noticeable on mobile, international traffic, or congested connections.

- Compression helps, but it doesn't erase cost. (See Brotli compression and Gzip compression.)

Render blocking

- Most CSS is render-blocking by default: the browser delays first paint until it has enough CSS to render safely.

- This is a core part of the critical rendering path and ties directly to render-blocking resources.

Parse + style + layout work

- The browser must parse CSS, build style rules, match selectors, and compute styles.

- That adds to main thread work, which can affect responsiveness and the ability to render quickly.

The Website Owner's perspective: If a landing page is "pretty fast" on your MacBook but feels sluggish on mid-tier Android, unused CSS is often part of the gap. Paid traffic magnifies this cost because more first-time visits means more cold-cache loads.

How it shows up in metrics

Unused CSS is not a Core Web Vital by itself. It's an input that often drives outcomes you do care about.

Metrics that commonly improve

- FCP (First Contentful Paint): Smaller, faster-to-apply CSS can get something on-screen sooner.

- LCP (Largest Contentful Paint): If the LCP element is waiting on CSS, reducing render-blocking CSS can pull LCP earlier.

- Speed Index (Speed Index): Faster visual completeness often follows reduced render blocking.

- INP (Interaction to Next Paint): Less styling overhead can reduce contention on the main thread, but this is less direct than JavaScript work.

Metrics that can get worse if you "fix" it wrong

- CLS (Cumulative Layout Shift): Deferring CSS without proper fallbacks can cause late style application and layout shifts. See zero layout shift.

Why lab and field can disagree

Unused CSS is typically flagged in lab tools (Lighthouse, synthetic tests), while business outcomes depend on field reality (device mix, connection mix, navigation patterns).

Use:

- Field vs lab data to set expectations

- CrUX data to validate whether the change moved real-user outcomes

How tools calculate unused CSS

Most "unused CSS" reporting is a form of coverage analysis:

- The browser observes which CSS rules are actually applied (selectors matching elements) during the measurement window.

- Bytes belonging to unapplied rules are counted as "unused" for that run.

This is why the number changes when you change:

- viewport (mobile vs desktop)

- cookie state (logged-in vs logged-out)

- A/B tests and personalization

- interaction (open menu, expand accordion, show modal)

- route or template (homepage vs PDP)

What influences the number most

1) One stylesheet for the whole site

- Common with themes, page builders, and "global" bundles.

- Every page downloads styling for every component – even if the component isn't present.

2) CSS frameworks and component libraries

- Large frameworks can be fine, but only when built with aggressive tree-shaking/purging and per-template delivery.

3) Third-party and app-injected CSS

- Tag managers, review widgets, chat tools, consent tools, and marketing apps can inject styles site-wide.

- Even if they "load later," they may still be discovered early and compete for bandwidth.

4) Overly generic selectors

- Deep selectors and complex matching can increase CPU time even if bytes are not huge.

When it's worth fixing

Removing unused CSS takes effort and can introduce regressions. Prioritize it when the payoff is real.

High-payoff scenarios

You should care a lot if:

- Key pages have large render-blocking CSS (especially on mobile)

- You rely on paid acquisition to cold traffic

- You have multiple templates with widely different components (home, category, PDP, blog)

- You're failing or borderline on Core Web Vitals and have already handled obvious issues (image sizing, server latency, etc.)

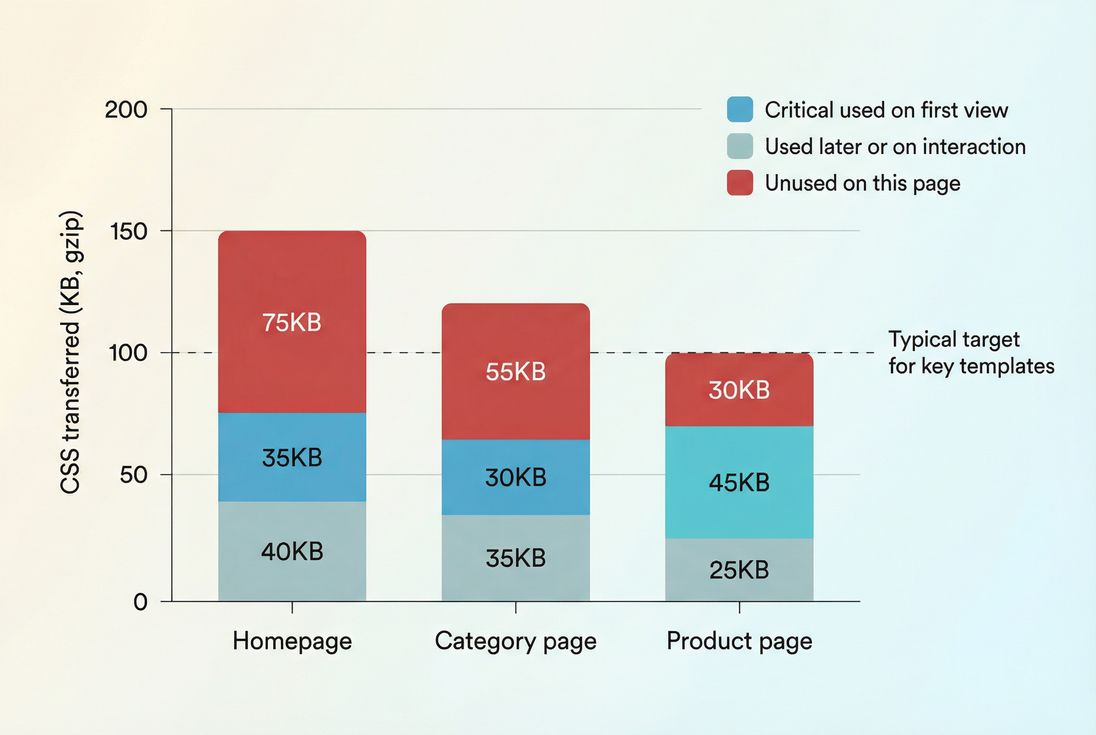

Practical benchmarks that guide decisions

These aren't universal rules, but they're useful targets for busy teams.

| Page type (mobile) | Healthy pattern | Warning sign |

|---|---|---|

| Homepage / landing | Small critical CSS + deferred rest | One big global CSS that blocks paint |

| Category / search | Template-scoped CSS | Lots of homepage/marketing section CSS loaded |

| Product page | PDP-specific CSS; minimal extras | Heavy "all widgets for all pages" CSS |

If you need a single heuristic for triage: optimize the CSS that blocks rendering on your top traffic and top revenue templates first.

The Website Owner's perspective: If engineering time is limited, focus on templates that directly map to revenue: paid landing pages, category pages, and product pages. Removing 40–80KB of unused render-blocking CSS on those pages is often more valuable than perfecting long-tail blog templates.

How to measure it reliably

You want two things:

- Identify which stylesheet(s) contain the waste

- Confirm whether that waste is render-blocking and present on important templates

Measurement workflow that works

Step 1: Run Lighthouse on key templates

- Look for "Reduce unused CSS" and note affected files.

- If you use PageVitals Lighthouse tests, start with the docs on Lighthouse tests so you can compare runs over time, not just once.

Step 2: Use Coverage in Chrome DevTools

- DevTools Coverage shows which rules are used on that page and which aren't.

- Use it to answer: "Is the waste in our main bundle, theme CSS, or an app/vendor file?"

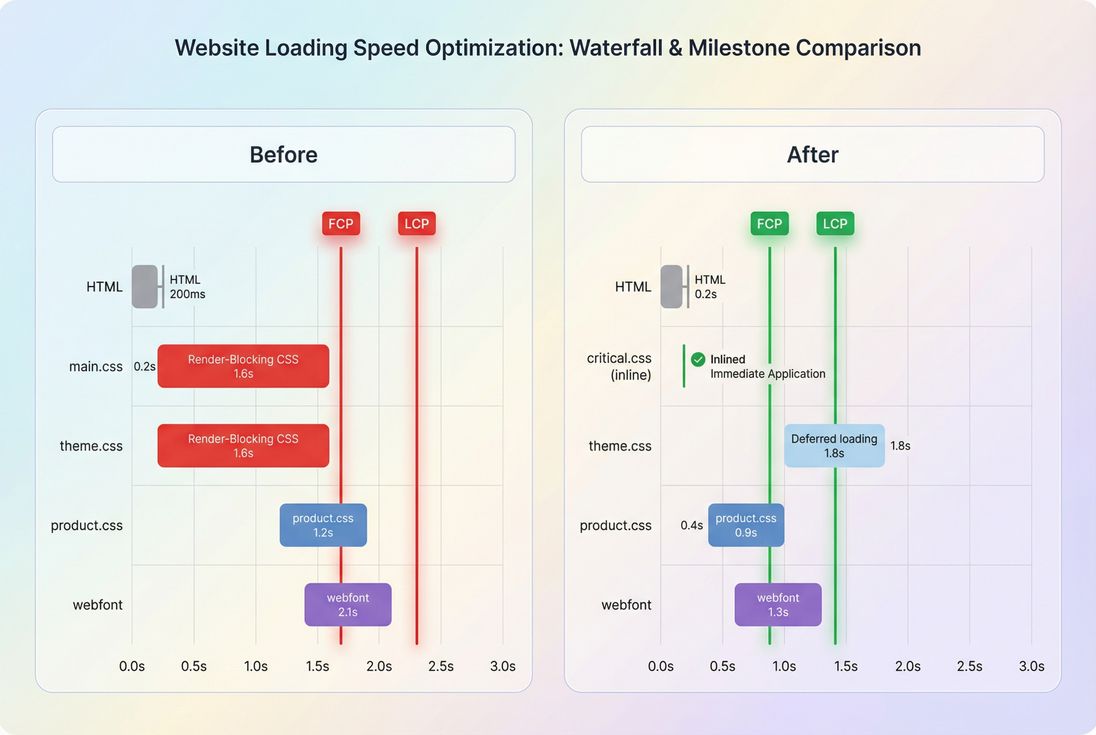

Step 3: Confirm in a waterfall

- Your goal is to reduce render-blocking bytes, not just "unused" bytes in a file loaded late.

- In PageVitals, the network request waterfall view is the fastest way to see which CSS files start early and block rendering.

Common measurement traps

- Testing one page and purging globally: CSS can be unused on the homepage but required on PDPs.

- Not testing mobile: Mobile viewport changes which rules apply, and mobile CPU makes CSS work more expensive.

- Not testing interactions: Menus, filters, modals, and validation states can depend on CSS that looks unused on load.

- Confusing "unused now" with "never used": Coverage is contextual.

To reduce risk, test multiple steps or templates in one go. If you're using PageVitals, multi-page journeys are what multistep tests are built for.

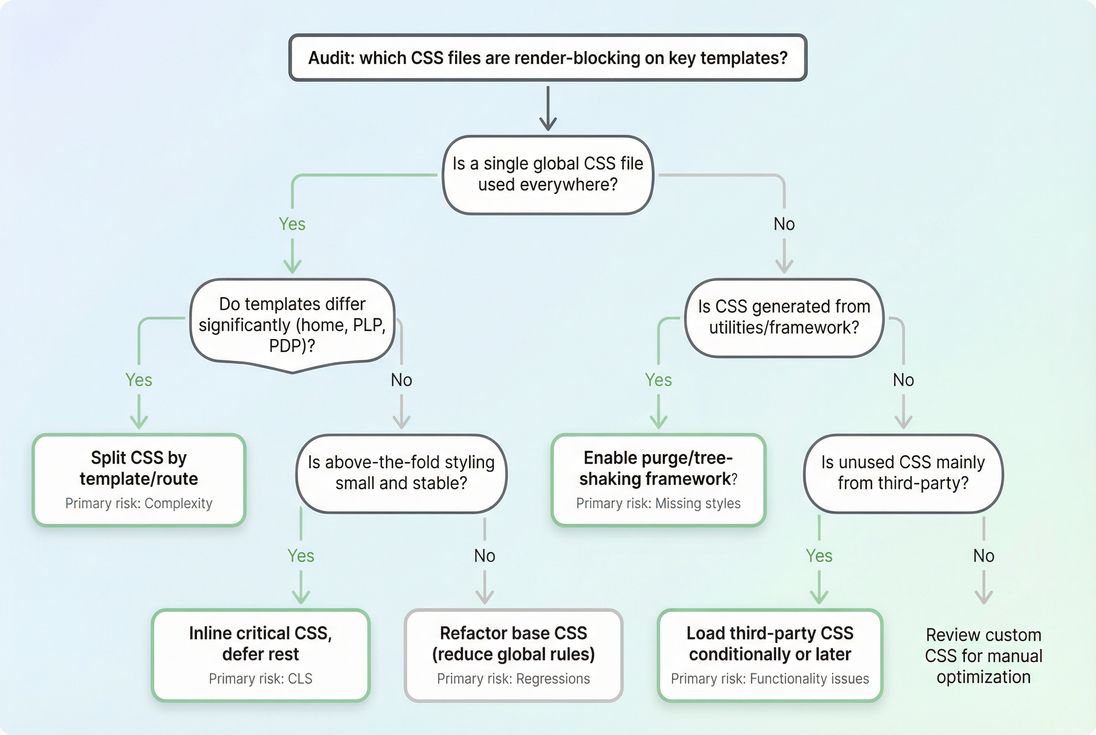

How to remove unused CSS safely

There are three main strategies. The right choice depends on your stack (Shopify, WordPress, custom React, etc.) and how much control you have.

Option 1: Split CSS by template or route

Best for: most e-commerce sites with distinct templates (home, PLP, PDP)

How it works:

- Instead of one global

main.css, producehome.css,category.css,product.css, etc. - Load only what the page needs, and keep genuinely global rules small.

This is essentially CSS-flavored code splitting.

Practical tips

- Start with one high-traffic template (often PDP).

- Keep a small "base" stylesheet for typography, grid, and shared components.

- Move page-specific blocks (carousels, reviews, size charts) into the template bundle.

Option 2: Inline critical CSS, defer the rest

Best for: marketing/landing pages where first paint is the business goal

Approach:

- Inline the minimum CSS needed for above-the-fold content.

- Load the full stylesheet later (or load non-critical CSS asynchronously).

This pairs naturally with:

- Above-the-fold optimization

- Critical CSS

- Understanding the critical rendering path

Risks to manage

- If your deferred CSS contains layout-affecting rules, you can trigger CLS.

- Inlining too much CSS bloats HTML and can reduce cache effectiveness.

Option 3: Purge unused selectors during build

Best for: modern build pipelines (Webpack/Vite), utility frameworks, component CSS

Tools like PurgeCSS (and built-in tooling in some frameworks) can remove selectors not found in your templates.

This is where teams get hurt because dynamic class names don't appear as static strings. Examples:

- classes assembled in JavaScript (

'btn-' + variant) - classes injected by CMS/page builders

- A/B testing tools swapping classes

- third-party widgets

Safety checklist

- Generate purge inputs from real templates for each page type.

- Maintain a safelist for dynamic patterns.

- Validate with visual regression checks on key templates and states.

A decision guide (what to do first)

| If your situation is… | Do this first | Why |

|---|---|---|

| One big theme stylesheet | Split by template | Biggest reduction in unused bytes per page |

| LCP is delayed on landing pages | Inline critical + defer | Targets render-blocking directly |

| Tailwind/utility CSS is huge | Purge at build | Usually the fastest byte win |

| Third-party apps inject CSS | Delay or conditionally load | Stops "site-wide tax" from optional features |

How to interpret changes over time

A drop in unused CSS is only meaningful if it translates into one (or more) of these outcomes:

- Render-blocking CSS got smaller (best case)

- Critical content styles arrived earlier

- Fewer bytes on first view for key templates (especially cold cache)

What a "good" improvement looks like

- Lighthouse shows fewer unused CSS bytes and

- the waterfall shows less time blocked on CSS and

- FCP/LCP improve in lab and ideally

- field metrics improve (via your RUM/CrUX trends)

If the unused CSS number drops but FCP/LCP don't change, it often means:

- you removed CSS that wasn't actually blocking (loaded late)

- the page is bottlenecked elsewhere (images, JS, TTFB)

Use supporting concepts to troubleshoot:

The Website Owner's perspective: A "CSS cleanup" that doesn't move LCP or conversion is still not a win. Treat unused CSS as a lever – then validate the lever moved the business metric you care about (checkout starts, add-to-cart rate, lead form submits).

How to keep CSS from coming back

Most teams fix unused CSS once… then slowly rebuild the problem through plugins, campaigns, and quick fixes.

Put guardrails in place

Set a CSS budget

- Define limits for render-blocking CSS on key templates.

- If you're using PageVitals, use performance budgets to make regressions visible.

Track key templates, not just homepage

- Homepages are often "optimized first" while PDPs and PLPs quietly gain weight.

- Consider multistep coverage for journeys (landing → category → product → cart). See multistep tests.

Make third-party CSS conditional

- If chat is only needed on support pages, don't ship its CSS on checkout.

- If reviews only appear on PDP, load that CSS there.

Keep caching strong

- Even if CSS is still larger than ideal, good caching reduces repeat-visit cost.

- Review Cache-Control headers, browser caching, and cache TTL.

Quick action plan (owner-friendly)

If you want a practical path that won't create chaos:

- Pick two templates: your top landing page + top product page.

- Measure: Lighthouse + DevTools Coverage + a waterfall view.

- Identify the biggest render-blocking stylesheet and where its unused bytes come from.

- Choose one strategy:

- split by template (best default)

- inline critical CSS (best for landing pages)

- purge selectors (best for modern build pipelines)

- Validate:

- check CLS risk

- confirm LCP movement in lab

- watch field data trends over days/weeks

Removing unused CSS is not about making styles "perfect." It's about shipping only what each page needs, when it needs it – so first impressions are fast, stable, and revenue-friendly.

Frequently asked questions

For most sites, the problem starts when a single render blocking stylesheet contains tens of kilobytes of rules the current page never uses. As a rule of thumb, if 30 to 50 percent of your above the fold CSS bytes are unused on key templates, it is worth fixing.

Often, yes, but indirectly. Less CSS can reduce render blocking time, which helps FCP and can pull LCP earlier on slower devices. It can also reduce main thread style and layout work. The biggest wins show up on mobile connections and mid tier phones.

Lighthouse reports unused CSS for the current page and viewport at the time of the test. Rules used on other pages, used only after interaction, or used at other breakpoints can look unused. Treat it as a page specific optimization signal, not a site wide deletion list.

It can be safe if you use template aware builds and strong safelists. The risk is removing classes added dynamically by themes, page builders, apps, or A B tests. Start with a single template, compare screenshots, test key interactions, then roll out gradually across templates.

Inlining critical CSS can help when your render blocking stylesheet is large, but it is not automatically the best answer. It adds HTML weight and can complicate caching. Many sites do better by splitting CSS per template, loading only what is needed, and deferring the rest safely.

Want to take PageVitals for a spin?

Page speed monitoring and alerting for your website. Get daily Lighthouse reports for all your pages. No installation needed.

Start my free trial